Mercantile trade was at the heart of British prosperity and overseas interests from the 18th to the 20th centuries. By the 18th century Britain had become the greatest European power in the East. This success was predominantly bound up with the government-licensed British East India Company, which had become the leading trading and political force in India.

In the late 18th century attempts were made to establish official relations with China by Lord George Macartney. The lavish embassy sent to Beijing as part of this British Government-backed mission was interpreted as humble tribute-bearing by the Chinese. The response to George III from the Qianlong Emperor noted that trade was out of the question, since Britain possessed nothing for which China had the slightest need. There were, however, many Chinese traders who were prepared to do business unofficially with foreigners. The trade in opium from India, the Opium War and ensuing British military expedition in 1840 resulted in the Qing government ceding compensation, Hong Kong Island and the opening of five ports to British traders. Twenty million people died in the bloody Taiping Rebellion in southern China, a massive civil war against the ruling Manchu-led Qing dynasty, which lasted from 1850 to 1864. Invasion by Japan in the late 19th century and the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 left the Qing dynasty severely weakened. A Chinese army rebellion in Wuchan sparked a series of mutinies culminating in the formation of the Republic of China in 1912, which would last in a series of guises until 1949. The last emperor, Puyi, was allowed to remain living in the Forbidden City in Beijing. The formation of the Chinese Republic brought to an end the Qing Dynasty and 2000 years of imperial rule.

As invasion and revolt continued to blight China during the early 20th century, porcelain of the most extraordinary quality continued to be made in Jingdezhen in the Jiangxi province. Some connoisseurs note this period of porcelain manufacture for its revival in quality, which they attribute to a number of schools and artists that emerged at this time. Chinese porcelain objects from this period often have inscriptions, usually in black enamel, which may include a combination of a poem, a signature or a cyclical date. Private workshops proliferated and flourished. The wares produced imitated designs from earlier periods, interpreting imperial designs to feed demand from American and British collectors like Sir Percival David. David’s collection includes many original examples of Chinese porcelain from the imperial collection, which can be seen at the British Museum in London.

We often discover Republic period Chinese porcelain in Sussex, which is finding increasing favour amongst collectors because of its quality. The early 20th century Chinese famille rose porcelain vase illustrated is from this period. The elongated ovoid body and flared neck are painted to one side with three birds perched on blossoming branches, to the other side with a gathering of children, elders and attendants beneath a pine tree. Note how these decorative panels are surrounded by lines of black text and red seals, typical of the Republic period. The vase is believed to have been painted by two leading artists from Jingdezhen. Measuring 60.5cm high, the vase sold at Toovey’s for £76,000.

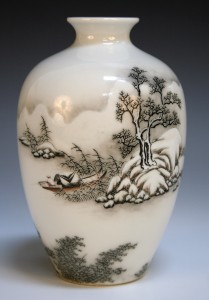

Not all Chinese porcelain of this period is so highly valued. The smaller Republic vase shown here, height 17cm, sold for £650. It is enamelled with a riverscape with a fishing boat by an island and has the typical text on the reverse.

This flourishing and revival in Chinese porcelain manufacture in the early 20th century allows us to once again glimpse the energetic and creative gifts of the Chinese people, which has gained them cultural prominence over millennia. Perhaps it is a rediscovery of these gifts which is allowing a revival of Chinese interests in the world today; only this time they are looking out into the world and reacquiring their cultural heritage.

Toovey’s Chinese porcelain specialist, Tom Rowsell, is always pleased to offer advice, whether you are interested in selling or acquiring Chinese objects in this boom market. He can be contacted at our offices.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 29th January 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.