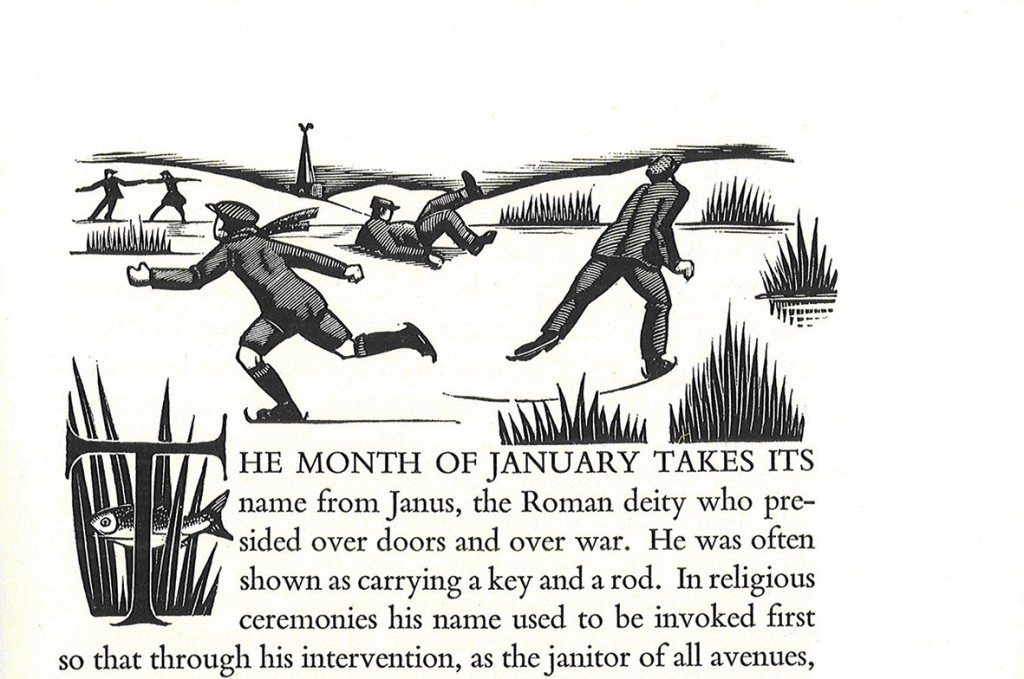

In the late 19th and 20th centuries many artists rediscovered their role as artisan artists and designers, as well as painters and sculptors of fine art. One of the ways that they expressed this was through making printed woodblock illustrations for fine books, printed by Private Presses.

The beginning of the Private Press movement is commonly attributed to William Morris, who in 1890 established the Kelmscott Press. William Morris led what was to become known as the Arts and Crafts Movement. Its principles were inspired by the writings of John Ruskin who mourned the effects of the industrial age on society and craftsmen. He advocated a return to an age of ‘free’ craftsman. It stood for traditional craftsmanship and simple forms often embellished with interpretations of romantic and medieval decoration including Gothic.

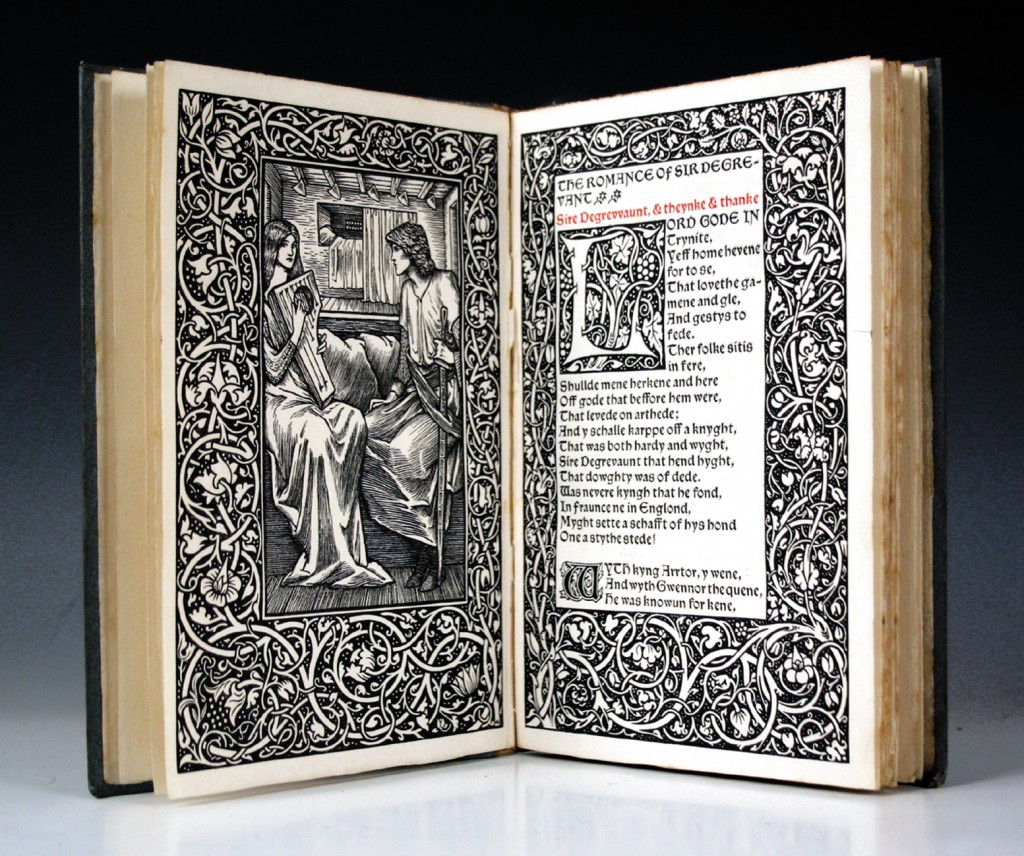

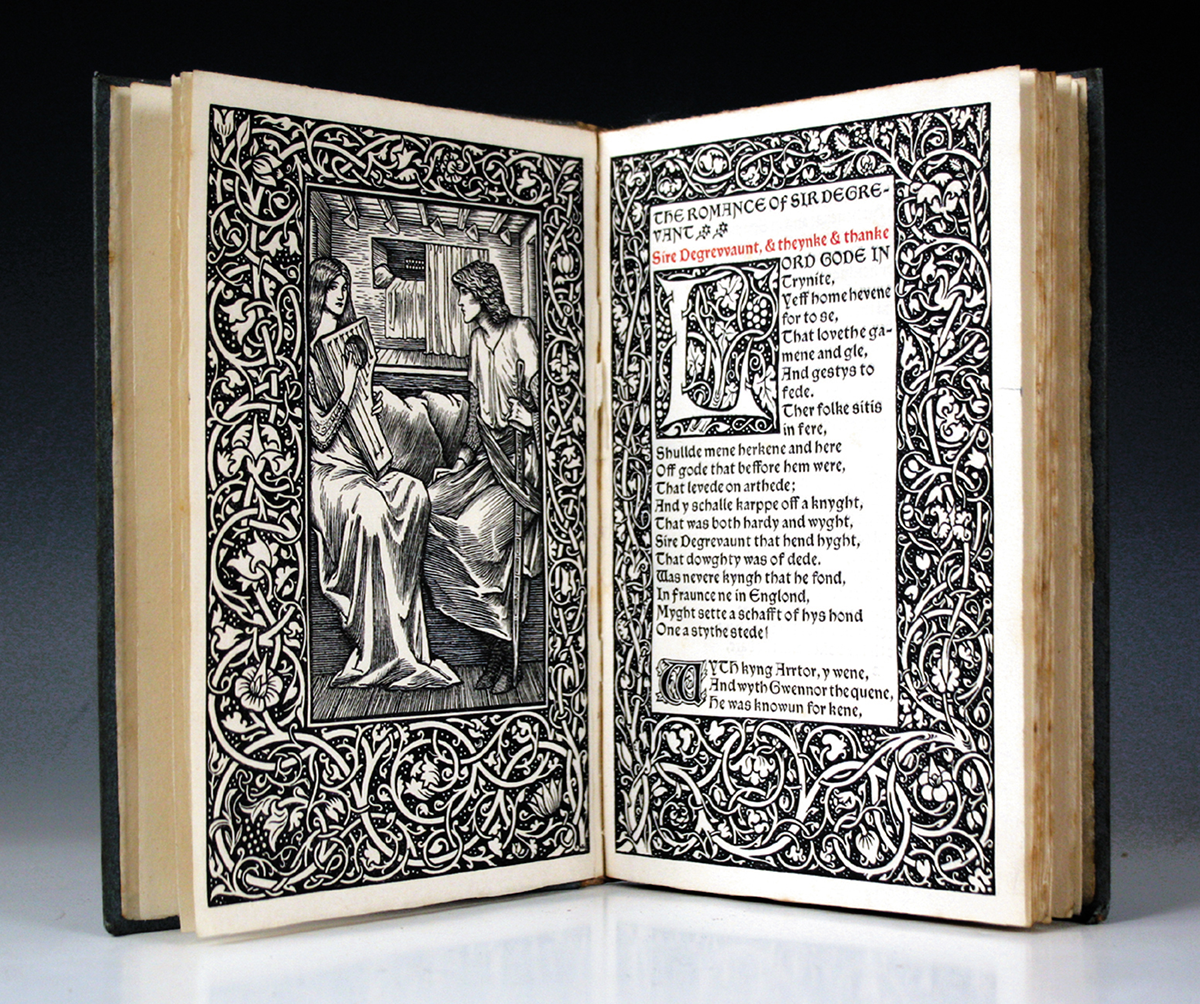

The Kelmscott Press woodcut frontispiece illustrated was designed by the Pre-Raphaelite, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, with whom William Morris worked in partnership on numerous designs, including churches. It depicts a scene from the book of ‘The Romance of Sire Degrevant’. The surround mirrors Morris’s own affection for the patterns of flower and leaf, which he too loved to design. The text is in Chaucer type, in red and black. Morris printed the book on 14th March 1896, a testament to his creative energy, even towards the end of his life. His principles, aesthetics, standards, qualities and techniques are strongly reflected in the Kelmscott Press project. He died on 3rd October 1896.

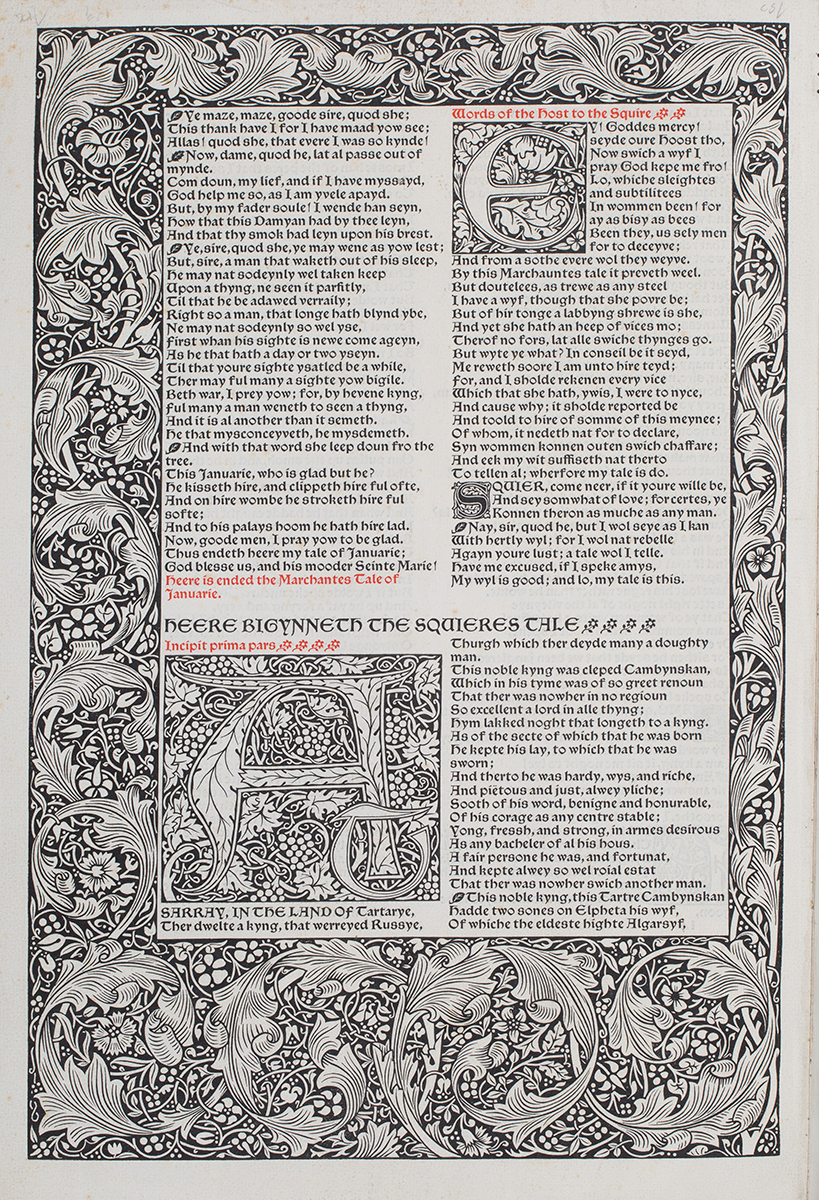

The page from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales provides another example of the decorative themes of the Kelmscott Press.

Technology has transformed the way we consume the printed word. But it is worth remembering that the Private Presses came into being as part of a reaction against the 19th century industrialised age. This was expressed through William Morris’s Arts and Crafts Movement. Like our spirited, independent local newspapers Private Press books remind us of the pleasure of engaging with the printed word. The smell, touch and sight of books speaks to our senses and delights us in a particular way.

So perhaps the future is in beautifully produced books. Certainly the demand for Antiquarian and Collectors’ books at Toovey’s has remained strong; a growth market for sellers and buyers alike. Tales of the demise of the printed word and the book, it would seem, have been over-exaggerated!