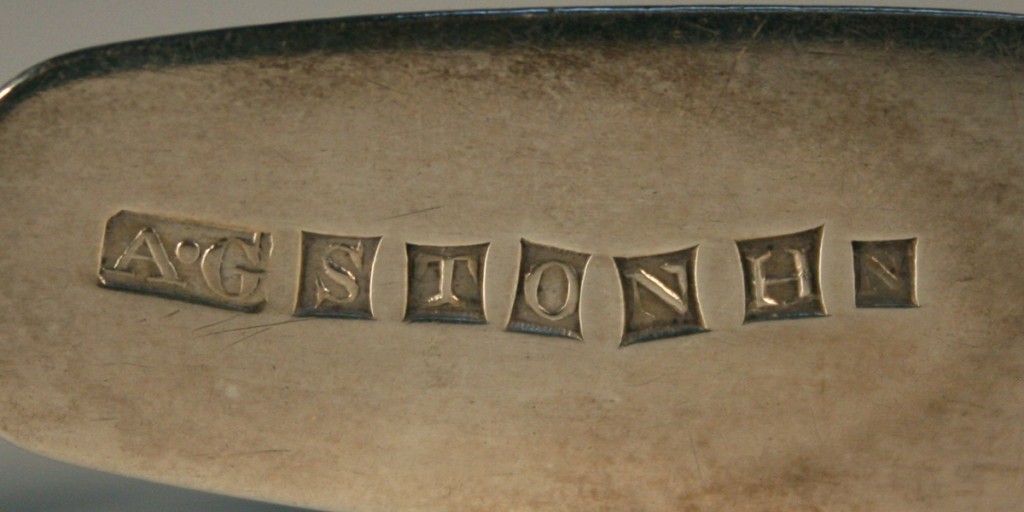

I have to own that I am passionate about tea. It is not just the diverse varieties of tea, or that it restores and revives, it is also the ritual. Each morning I delight in warming and filling my silver tea pot, allowing the tea to steep beneath its cosy before pouring the first cup of the day and preparing my thermos. Nothing beats the flavour of tea made in a silver teapot!

Tea has been drunk in China for some 4000 years. However, it was not introduced to Britain and Europe until the 17th century.

On the 25th September 1660 Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that he ‘did send for a cupp of tee (a China drink) of which I never drank before’. It is thought Thomas Garroway of Exchange Alley, London, first sold tea in England in 1657. It was made fashionable by Charles II’s Portuguese queen, Catherine of Braganza who brought her love of tea to the English court.

Early English teapots from the 17th and the early 18th centuries are rare and tend to be small as tea was very expensive. By the later 18th and early 19th centuries tea had become a little more affordable whilst maintaining its fashionable status.

Tea related objects proliferated including porcelain. Take for example the Flight, Barr & Barr Worcester porcelain part tea service illustrated here. The Worcester factory had been formed in 1752 when the factories of Benjamin Lund and Dr John Wall had been united. Dr Wall retired in 1774 and in 1783 the factory was purchased by the firm’s London agent, John Flight. His son, Joseph, would enter into partnership with Martin Barr in 1792 and the company became Flight & Barr. As the partnership evolved so did the name and after Martin’s death in 1813 the company became Flight, Barr & Barr. During this last period the quality of the wares was outstanding and included tea services typified by fine, restrained decoration. This tea service dates from around 1820. The bands of brown and gilt leaf sprays are united with the form of the pieces, the design brought alive by the small red flowers. It realised £1900 at a recent Toovey’s specialist auction.

Tea related objects were often made in silver. In the later 18th century the rococo taste was fashionable. The George III Scottish silver tea pot is of inverted pear form and was assayed in Edinburgh in 1777. The chased decoration reflects the fashion for the rococo at this date with its opposing scroll cartouche and flower festoons. It sold for £950.

The three early George III silver tea caddies reflect the value of tea in the mid-18th century and are also in the rococo taste. Their flower finials and rectangular bombé outline are decorated with chased, spiral reeded bands and cornered foliate borders. The scroll and scallop aprons incorporate scalloped feet. Made by the silversmith John Foster and assayed in London in 1766, with their contemporary walnut case they realised £5100 at Toovey’s.

The fashion for tea related objects is once again in revival. Silver tea pots can still be bought reasonably at auction but prices have risen. Perhaps it’s time you treated yourself to tea and enjoyed the delight in silver and porcelain. After all tea always tastes better when it has been made in a silver teapot and is savoured in porcelain cups!

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 25th February 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.