In the 20th century many artists rediscovered their role as artisan artists and designers, as well as painters and sculptors of fine art. One of the ways that this was expressed was by making printed woodblock illustrations for fine books, printed by private presses.

The beginning of the British private press movement is commonly attributed to William Morris, who established the Kelmscott Press in 1890. William Morris led what was to become known as the Arts and Crafts movement. Its principles were inspired by the writings of John Ruskin, who mourned the effects of the industrial age on society and craftsmen. He advocated a return to an age of the ‘free’ craftsman. The movement stood for traditional craftsmanship and simple forms, often embellished with interpretations of romantic and medieval decoration, including Gothic.

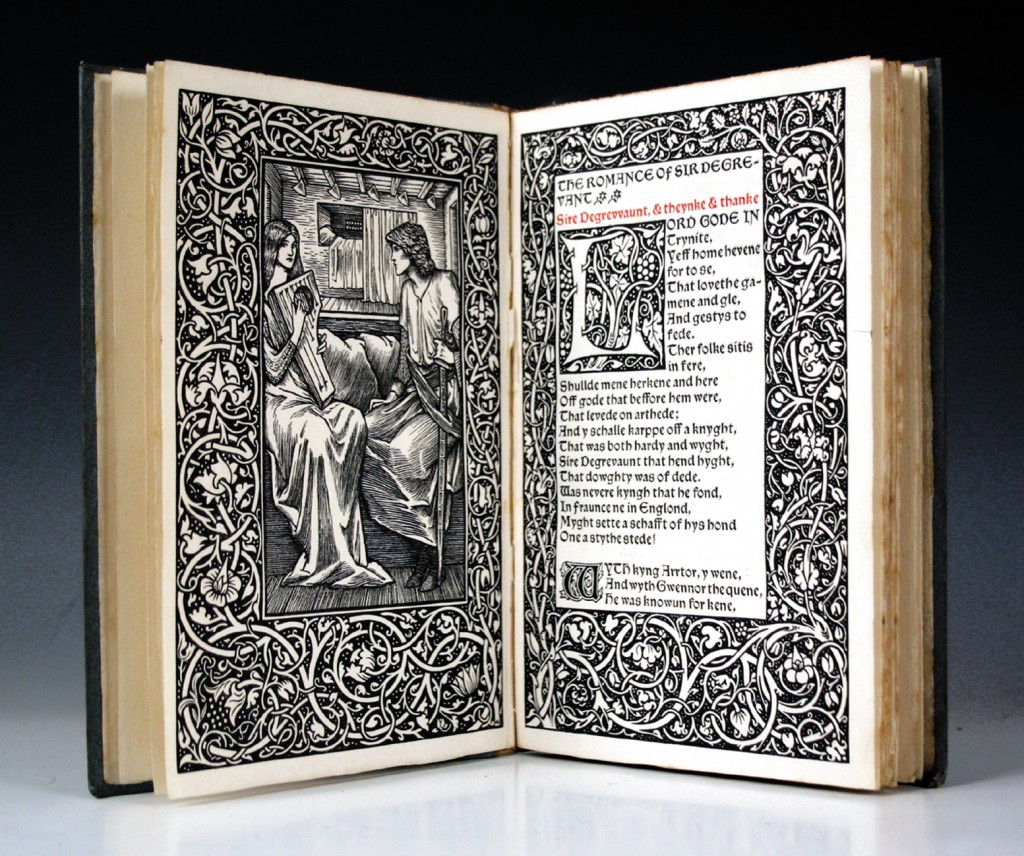

The Kelmscott Press woodcut frontispiece illustrated was designed by the Pre-Raphaelite Sir Edward Burne-Jones, with whom William Morris worked in partnership on numerous designs, including churches. It depicts a scene from the book of ‘The Romance of Sire Degrevant’. The surround mirrors Morris’s own affection for the patterns of flower and leaf, which he too loved to design. The text is in Chaucer type, in red and black. Morris printed the book on 14th March 1896, a testament to his creative energy, even towards the end of his life. His principles, aesthetics, standards, qualities and techniques are strongly reflected in the Kelmscott Press project. He died on 3rd October 1896. The book was eventually issued by the Trustees, in an edition of 350 copies, in November 1897.

Other Victorian presses included the Eragny Press, run by the artist Lucien Pissarro and his wife, and C.R. Ashbee’s Essex House Press, which formed part of the activities of the famous Guild of Handicraft.

Perhaps the two most notable private presses in Sussex for the prospective collector to look out for are the Vine Press, Steyning, and the Ditchling Press, Ditchling. Both were operating in the early 20th century between the wars. Vine Press reflected the passions of its owner, the English poet and writer Victor Benjamin Neuberg. The Ditchling Press was part of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic. At this time it represented an experiment of artists living and working together in community under the leadership of its founders: Eric Gill, Hilary Pepler and Desmond Chute.

Private press books published in the 20th century continued to be illustrated by leading British artists. Many of these are printed in limited editions, signed by both author and artist. The illustrations are often printed from the woodblock upon which the artist drew and carved the image. They are an accessible and relatively affordable way to collect their work.

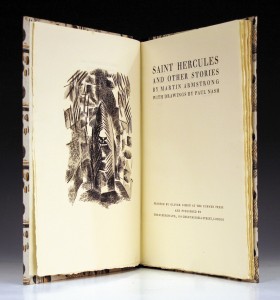

The Sussex collector may also be drawn to artists working in the county. Take for example Paul Nash, who, as readers of this column will know, worked in Sussex and whose work is currently being exhibited at Pallant House Gallery as part of the Clare Neilson Gift. This copy of ‘Saint Hercules and Other Stories’ is owned by a local private collector, who purchased it at a Toovey’s specialist book auction a few years ago for £400. The author, Martin Armstrong, based these stories on interpretations of tales including those from Palladius’s ‘Paradise of the Holy Fathers’ and Petronius’s ‘Satyricon’. His excellent narrative is complemented by five beautiful illustrations by Paul Nash. The book is numbered 26 of an edition of just 310. It was printed by Oliver Simon at the Curwen Press in 1927, on hand-made Zander’s paper. Private press books, like this one, connect us with these artisans – the artist, author and printer – in what was a very personal and direct creative process.

Advances in printing in the 19th century revolutionised the production of books. Today, technology is once again revolutionising how books are made available to us. Indeed, there is much debate about the survival of the printed book in the face of Kindles, iPads and tablet PCs. But it is worth remembering that the private presses came into being as part of a reaction against the industrialised age. This was expressed through William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement. Perhaps this window into our past might provide a window into our future. Private press books remind us of the pleasure of engaging with the printed word; the smell, touch and sight of books speaks to our senses and delights us in a particular way. So perhaps the future is in beautifully produced books. Certainly the demand for antiquarian and collectors’ books at Toovey’s has remained strong – a growth market for sellers and buyers alike. Tales of the demise of the book, it would seem, have been over-exaggerated!

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 17th April 2013 in the West Sussex Gazette.