As March draws to a close it marks the procession towards the end of the great reflective Christian season of Lent. The name Lent probably has Anglo-Saxon origins coming from a word meaning ‘spring’, which refers to lengthening days. Recently we have been blessed with some beautiful bright days punctuating the grey skies.

Last Sunday I found myself in the company of my cousins, Colin and Paulette De La Haye. They farm Jersey Royal potatoes on land bought by Paulette’s family in the late 19th century. Bel Val Farm sits confidently in its landscape in the North East of the Island of Jersey. For them this is not work, it is a way of life filled with dedication and love.

Our conversation moves, as it usually does, from the world of fine art auctioneering to the important business of this year’s potato season. One of my great delights of the year are the first Jersey Royal potatoes. There is something hopeful in their arrival. Their flavour, texture and colour, for me, marks them as the finest potatoes in the world, especially when they come from Bel Val Farm!

I comment on the chill in the wind and note that the covers are back on the early crop. Colin has the most extraordinary connection with the land. He observes and understands the language of the seasons and nature in a remarkable way. He says “We’re expecting the largest tide of the year tonight, it’s a full moon and the tide comes with the moon. If you are going to get a frost it will be with the Easter moon. Frost comes with the tide this time of year.”

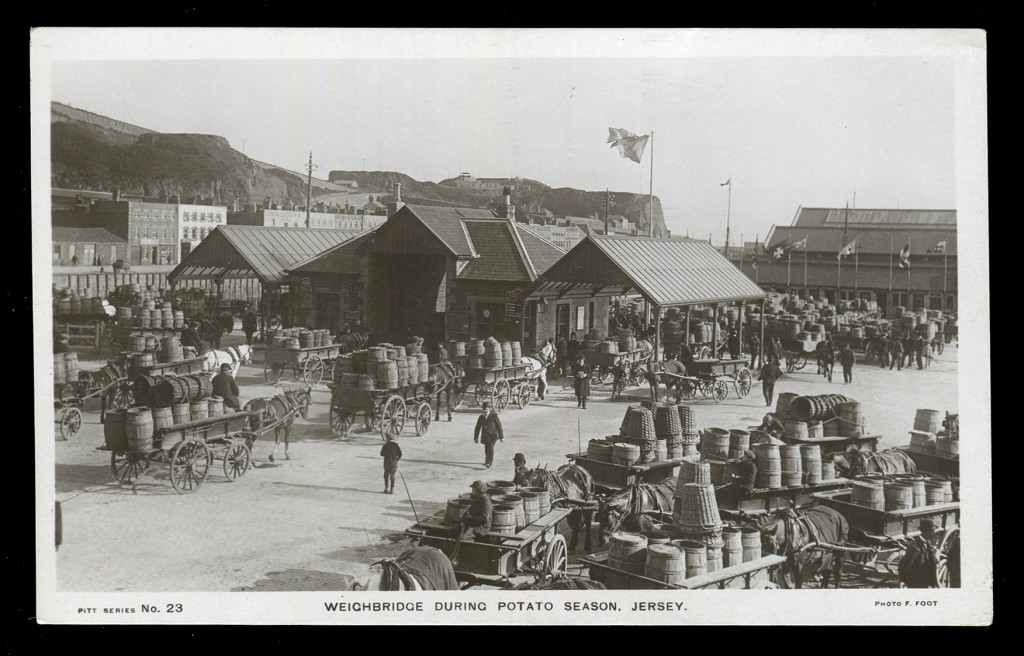

Jersey Royals have been a major export for the Island for more than a century. The postcard illustrated here was sold in a Toovey’s specialist Paper Collectables auction. It depicts the bustle at the harbour during the potato season in the early 20th century. At this time there were hundreds of small farms and growers. Today there are just twenty growers. The Jersey Royal is one of the few truly seasonal crops. Its season lasts just a few months. Each year approximately 30,000 tonnes of Jersey Royals are exported to the UK, worth some £29 million pounds. The value of this crop comes from its unique flavour and that it is one of the earliest new potatoes of the season.

Being early to the market is important to a successful season as there is a premium to the price. Colin explains that each potato seed is individually stood up by hand in some 20,000 boxes over the winter months. They are stored in their potato sheds, some of which are built of granite and overlook the bay. With the eyes facing up it gives the seed an advantage once planted. The earliest Jersey Royals traditionally came from the steep sloping fields known as côtil which catch the sun and guard against the frost. Colin and Paulette’s côtil are so steep that they have to be ploughed with an ancient horse plough attached to a winch at the top of the slope. Vraic, gathered seaweed, is still put on some of the crop to improve the condition of the soil and the flavour.

Colin’s organisation, care and stewardship of the land always impresses me. He and his team will plough, plant, prepare and cover a field in a single day. But there is always the unknown in farming and in particular the weather. I ask Colin how this season is looking, he replies optimistically, as he always does “We haven’t had any frost since the 8th and 9th of January so that’s been ok.” He pauses and smiles wryly and continues “We’ll see what tonight brings. We need a bit of sun now to warm them up.”

Colin’s Jersey accent reminds me that whilst Jersey is part of the British Isles its rich history and traditions mark this proud Island people’s independence.

Always optimistic, attentive to the seasons and tides Colin is rooted in his landscape. Paulette and Colin’s hard work, stewardship and generosity is always inspiring and is to be admired.

Lent affords us time to reflect, a punctuation mark in our busy lives, a time to be reminded of things that we might, for a moment, have forgotten and to rediscover the familiar anew. So look out for the first of the seasons Jersey Royals they may well be from Bel Val Farm!

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 25th March 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.