Pallant House Gallery’s Artistic Director, Simon Martin, opened their latest exhibition ‘David Jones: Vision and Memory’ last Friday. This timely retrospective provides an extraordinary insight into the life and work of this talented British artist who, between 1921 and 1924, was a member of Eric Gill’s Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic in Ditchling, Sussex.

David Jones (1895-1974) worked as a painter, engraver, poet and maker of inscriptions. He responded with a lyrical delight to the visual world around him. But there is also a mystical, timeless quality to his work, rooted in the memory of the long and ancient procession of human history. In 1936 the famous art historian, Kenneth Clark, described him as ‘in many ways, the most gifted of artists of all the young British painters’, adding in the late 1960s that Jones was ‘absolutely unique – a remarkable genius’.

My passion for Modern British Art began at Jim Ede’s home, Kettles Yard, in Cambridge. Jim Ede championed many of the leading artists of the 1920s and 1930s whilst an assistant curator at the Tate gallery in London. It was at Kettles Yard, amongst the work of Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Naum Gabo and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, that I first encountered David Jones’ watercolours and prints. Amongst these was the expressive work ‘Flora in Calix Light’. Jones converted to Roman Catholicism whilst at Ditchling and his faith remained one of the recurrent influences on his art and writing. In the 1950s Jones’ horizons began to come in on him and his attention moved from a delight in the world outside to the interior. The resulting still lifes are considered to be amongst his best works. ‘Flora in Calix Light’ has many of the common themes of these watercolours. The large, central glass goblet resembles the chalice of the Mass. There is an abundance in the garden flowers which fill it. The three glass chalices represent the scene of the crucifixion. They are charged with a translucent light, the white gouache heightening our sense of the luminous. Through the open window we glimpse a tree which reminds the viewer of the cross. This reflective painting captures the mystery of the Passion narratives through its rich symbolism, whilst the Christian iconography is implicit rather than explicit. There is a connection with David Jones’ meditation on the unity of all creation in the presence of God, ‘The Anathemata’, which was published in 1952.

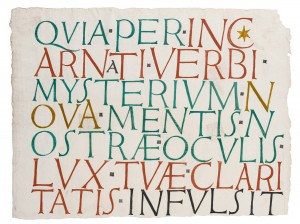

From the 1940s onwards David Jones embarked on a series of painted inscriptions. They are amongst the most beautiful images in this exhibition. Initially he produced them as greetings cards to friends. There is a playful quality to them as the artist wilfully misspells words and mixes languages. But these are meditative pieces which demand the full attention of the viewer. They embody an understanding of the true presence of Jesus Christ in the Mass and as ‘the Word made flesh’ as expressed in ‘Quia Per Incarnati’.

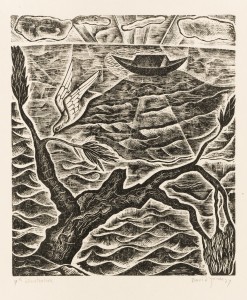

The exhibition illustrates the development of, and influences on, the work of this complex artist in an accessible way. It allows us to see the consistent quality of line apparent throughout David Jones’ career and not least in his earlier wood engraved illustrations like ‘The Dove’.

‘David Jones: Vision and Memory’ will reward you whether you are familiar with the artist’s work or discovering him for the first time. You cannot fail to be delighted by this remarkable modern British artist with such strong links to Sussex. I am pleased that Toovey’s is amongst the headline sponsors of this insightful exhibition which runs until 21st February 2016 at the Pallant House Gallery, 9 North Pallant, Chichester, PO19 1TJ. For more information about the gallery’s current exhibition program go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 28th October 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.