For many years the remarkable wall paintings at the little known Saxon church, St John the Baptist, Clayton, West Sussex, were thought to date from the 12th century. This established view is being challenged and although opinion remains divided it seems increasingly likely that they are late Saxon, dating from the mid-11th century.

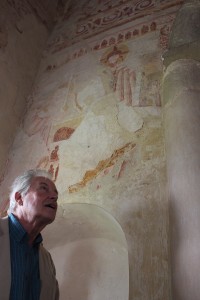

To explore this I meet my friend, Professor Robin Milner-Gulland, at Clayton. For some time Robin has been a leading voice in promoting the arguments for re-attributing these wonderful paintings to the late Saxon period. He believes that it is likely they were painted in the mid-11th century, before the Norman Conquest in 1066. From the time of Alfred the Great in the 9th century the Saxon kingdom of Wessex, of which we were a part, was a centre for the arts with influence drawn from France and the Holy Roman Empire.

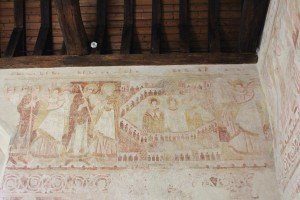

The church at Clayton sits in the folds of the South Downs National Park beneath the Jack and Jill windmills. The interior of the church is painted with some of the finest and most important fresco wall paintings in the country. There is a majesty and fluidity in the elongated figures whose tunics have a rare quality of movement and softness. The scheme is beautifully worked out representing stories from the Bible’s book of Revelations. Indeed, the church is believed to have originally been dedicated to All Saints. Unusually the artist predominately used lime white in the tunics which gifts the figures with a luminous quality. There is some charcoal used which can appear blue to us after the passage of time. The red and yellow ochre hues unite these frescoes with the churches at Hardham, Coombes and Plumpton and are common to most early wall-paintings.

Frescoes are wall paintings painted directly on to plaster while it is still wet. The artist has to work quickly and as the plaster dries the pigments and image are fixed. Robin explains “The quality of the Saxon mortar has given these wall paintings an outstanding durability.”

The depiction of Christ the King above the chancel arch is exquisitely conceived. Jesus sits enthroned with His arms raised in blessing within an oval shaped border known as a mandorla. Supported by two winged angels Christ is flanked by saints who appear to move about in easy conversation with one another. I also love the image of the New Jerusalem descending from heaven so that God will live among us once again in a new and perfected creation with no more suffering and injustice. The hexagonal city is finely executed.

Robin says “It is generally accepted that the fabric of the church is Saxon in its construction and proportion.” I remark on the height and the finesse of the chancel arch. He responds “There is a grandeur at Clayton. The walls are over twenty feet high and the chancel arch is awe-inspiring.” He continues enthusiastically “The overall processional composition, the ornamental borders, especially the lower palmettes dividing the scheme on the chancel wall, the movement in the folds of the massed hierarchical figures’ clothes and the lack of a hard outline in the depiction of many of them, all indicate a date in the 11th century” The compositional scheme certainly shows a cohesive sensitivity to the architecture of the interior.

Eve Baker worked to conserve these frescoes. Importantly she discovered that they were painted as true frescoes whilst the plaster was still wet and are the lowest layer of plaster on the wall surface. Robin suggests that it is unlikely that the church would have been left un-plastered after its completion. If, as seems likely, this is the case then the wall-paintings are contemporary to the building and are late Saxon. Those academics who argue that these paintings are later, from the 12th century, are suggesting that Clayton was later plastered some fifty to a hundred years after the church’s completion and painted in an earlier archaic style. To my mind their argument is unconvincing.

For me, when Baker’s conclusions are combined with the early style of the composition, and its depiction of the figures, it highlights the characteristics and influence of the Anglo Saxons in the painter’s hand.

Using the methods of contemporary art criticism, I think there is an increasingly strong argument for questioning the previously accepted view that the paintings at Clayton, Hardham, Coombes and Plumpton were united in their stylistic qualities and influences by the Benedictine Cluniac priory at Lewes. Whilst there are similarities there are also significant differences.

I am more and more convinced that these churches, once known as the ‘Lewes Group’, contain frescoes from the Saxon period and I look forward to returning to Hardham, Coombes and Plumpton in the New Year to re-examine the examples there.

This weekend the church celebrates the Feast of Christ the King and celebrates his authority. How fitting that this is so wonderfully depicted at St John the Baptist, Clayton. There will be a service of Holy Communion celebrated there this Sunday, 23rd November at 11.15am, where you can worship and inhabit this remarkable Church and its frescoes, as people have done since Saxon times. The church is usually open during the day and is one of my favourite places to stop and pray. Our thanks should go to the Revd. Christopher Powell, the churchwardens, Jill Rogers and Jim Coppen and the congregation who make this a living, prayerful place for us all.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 19th November 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.