Over the centuries, it has always been the gift of great artists to reflect upon the world we all share and to allow us, through their work, to glimpse something of what lies beyond our immediate perception. The 20th century brought the shared and shocking experience of war to two generations. In 1944, the artist Hans Feibusch in his book ‘Mural Painting’ wrote, “The men who come home from the war, and all the rest of us, have seen too much horror and evil; when we close our eyes terrible sights haunt us; the world is seething with bestiality; and it is all man’s doing. Only the most profound, tragic, moving and sublime vision can redeem us. The voice of the Church should be heard loud over the thunderstorm; and the artist should be her mouth piece as of old.”

It has often been the role of enlightened patrons to enable artists to express their visions. In 1942, as bombs fell upon Britain, Walter Hussey, on Kenneth Clark’s recommendation, commissioned Henry Moore to carve ‘Madonna and Child’ in the warm hues of Hornton stone at St. Matthew’s, Northampton, where he was vicar. As the sculpture was nearing completion, Hussey talked to Moore about a number of artists he was considering for a large painting in the south transept, opposite ‘Madonna and Child’. Henry Moore unhesitatingly recommended Graham Sutherland.

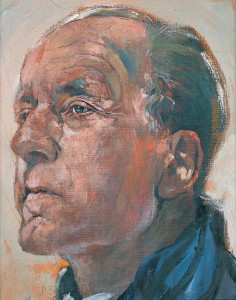

Hussey had in mind the Agony in the Garden as a subject. Sutherland confessed his ambition “to do a Crucifixion of a significant size” and Hussey agreed. Writing of the finished work, Kenneth Clark, then Director of the National Gallery and responsible for the War Artists project, said, “Sutherland’s Crucifixion is the successor to the Crucifixion of Grünewald and the early Italians.”

In 1955, Winston Churchill’s last ecclesiastical appointment was to install Walter Hussey as Dean of Chichester Cathedral, where his influence bore much fruit. Hussey can be credited with commissioning most of the exemplary 20th century art at Chichester Cathedral. How appropriate, then, that Walter Hussey’s gift of much of his art collection to Chichester should reside at Pallant House Gallery.

Sutherland’s 1947 version of the ‘Crucifixion’ from the Hussey Bequest is displayed at Pallant House Gallery. It illustrates the artist’s obsession with thorns as metaphors for human cruelty; their jagged lines are reflected throughout the composition. The American military published a book of photographs which featured scenes of the Nazi concentration camps, including images of those held captive at Belsen, Auschwitz and Buchenwald. To Sutherland, “many of the tortured bodies looked like figures deposed from crosses” and he acknowledged the influence of these photographs on his Crucifixions. Here, Jesus Christ’s body hangs lifeless upon the cross, the shocking red of his blood accentuated by the fertile green. There is agony in the body’s posture, the weight clearly visible in the angular shoulders, chest and distorted stomach. This is a God who understands and shares in human suffering. Graham Sutherland, a Roman Catholic, was sustained by his Christian faith all his life. He commented that he was drawn to the subject of the Crucifixion because of its duality. He noted that the Crucifixion “is the most tragic of all themes yet inherent in it is the promise of salvation”.

In Sutherland’s versions, a generation united in their common story finally had depictions of the Crucifixion which reflected their experience of the world and yet spoke loudly of the triumph of hope in response to the tragedy of violence and war.

Graham Sutherland’s vibrant oil on canvas ‘Noli me tangere’ of 1961 was commissioned by Walter Hussey for the St Mary Magdalene Chapel in Chichester Cathedral.

The painting depicts the moment on that first Easter morning when Mary Magdalene becomes aware that she is in the presence of her risen Lord who has just spoken her name. As she reaches out to touch him his gesture stops her. The angular composition of the figures, plants and staircase allude to the Passion narratives which lead up to and include Jesus’ crucifixion. At the centre of the painting is Jesus Christ dressed in white symbolising his holiness and purity. Christ’s finger points towards God the Father symbolising His presence. Graham Sutherland invites us into the narrative at this liminal moment so that we, like Mary, might acknowledge Jesus, our creator, teacher and friend, as advocate and redeemer of the whole world.

Here we witness the triumph of hope and love over evil and hatred.

There are a number of special services and concerts at Chichester Cathedral in the coming days to mark Holy Week and Easter. For more information and times go to www.chichestercathedral.org.uk. To find out more about Pallant House Gallery, 9 North Pallant, Chichester, PO19 1TJ, its collections, exhibitions and opening times go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 1st April 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.