There has been much debate around national identity in relation to the forthcoming vote this week on whether Scotland will remain part of the United Kingdom. The undisputed qualities of the Scottish people and their contribution to our nation’s history have rightly been celebrated. Nations, like families and communities, are bound together by the telling of these shared stories – a common narrative of joy and sorrow.

These debates have caused me to consider what the English bring to our nation. For me, one of our major contributions is the way in which the story of our island’s life, history and Christian faith is articulated and marked by the Church of England in each generation. It is from the Church that the qualities of tolerance and fairness come, qualities which shape our national character.

I am proud that tolerance and fairness are still to be found at the heart of our nation. These qualities were seeded, though not perfected, during the reign of Elizabeth I (1533-1603). There had been much conflict and bloodshed after Henry VIII’s break with Rome, as Roman Catholics and Protestants each sought to establish their authority and particular understandings of the Christian faith in England. Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558. Her first aim was to return England to the Protestant faith. What she and her advisors created was a church which was, and remains, both Catholic and Reformed.

The Act of Supremacy of 1558 established Elizabeth as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. In the same year the Act of Uniformity was passed by a narrow majority in Parliament. It required the population to attend an Anglican church each Sunday. In addition, it specified that a new version of the Book of Common Prayer be used.

After Parliament had been dismissed, a series of Royal Injunctions were courageously passed by Elizabeth I in 1559. The result of this was that the wording of the liturgy for Holy Communion remained open to a variety of interpretations. This allowed Christians holding differing understandings of the nature of the consecrated bread and wine to receive this sacrament with integrity in the privacy of their own hearts. Elizabeth famously declared that she did not wish to ‘make windows into men’s souls’ on the basis that ‘there is only one Jesus Christ and all the rest is a dispute over trifles’. The Royal Injunctions ensured much continuity with the practices of the Roman Catholic past. These included requirements that ministers wear vestments and use wafers in the place of baker’s bread.

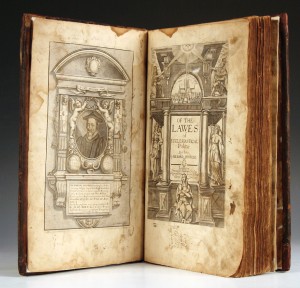

It was the famous Anglican theologian Richard Hooker (1554-1600), in ‘Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie’, who emphasised the importance of reason, tolerance and the value of tradition, which are at the heart of the English nation and her Church.

What this means in practice is that our common narrative, our tradition, allows us to be confident of who we are. Reason allows for open-minded and open-hearted questioning and for difference of opinion. Together the two afford us tolerance and we can celebrate diversity and difference in a spirit of love and understanding, rather than fear and ignorance.

These qualities have blessed our nation and our Church. It is my prayer that we will allow these qualities to be central to our continued, shared national story. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II still holds the title ‘Defender of the Faith and Supreme Governor of the Church of England’, fitting as we live in a nation which aspires to tolerance and fairness in this second great Elizabethan age.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 17th September 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.