The English love affair with the garden has been conducted over centuries.

The influence of the Arts and Crafts movement led by designers like Gertrude Jekyll and Edwin Lutyens combined structured layouts with more naturalistic informal planting. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries artists captured this expression of Englishness and our love affair with gardens in their art.

These equalities are apparent in A Path of Roses by the Anglo-American artist George Henry Boughton (1833-1905). Boughton was born in Norwich. His family emigrated to America in 1835 when he was just two. He would grow up in New York. Throughout his life he journeyed between and exhibited in America and London. He was elected as a Royal Academician in 1896. In A Path of Roses Boughton depicts a young girl walking in a rose garden, her cat upon her shoulder. This stylized scene provides an American romantic interpretation of the English affair with gardens giving expression to the Pre-Raphaelite and Arts and Crafts voices prevalent in British art at the time. The light, palette and composition create a stillness, it is as though we glimpse a moment out of time. The oil painting, which sold at Toovey’s for £2200, was a cabinet sized version of the artist’s 1875 Royal Academy exhibited work of the same title.

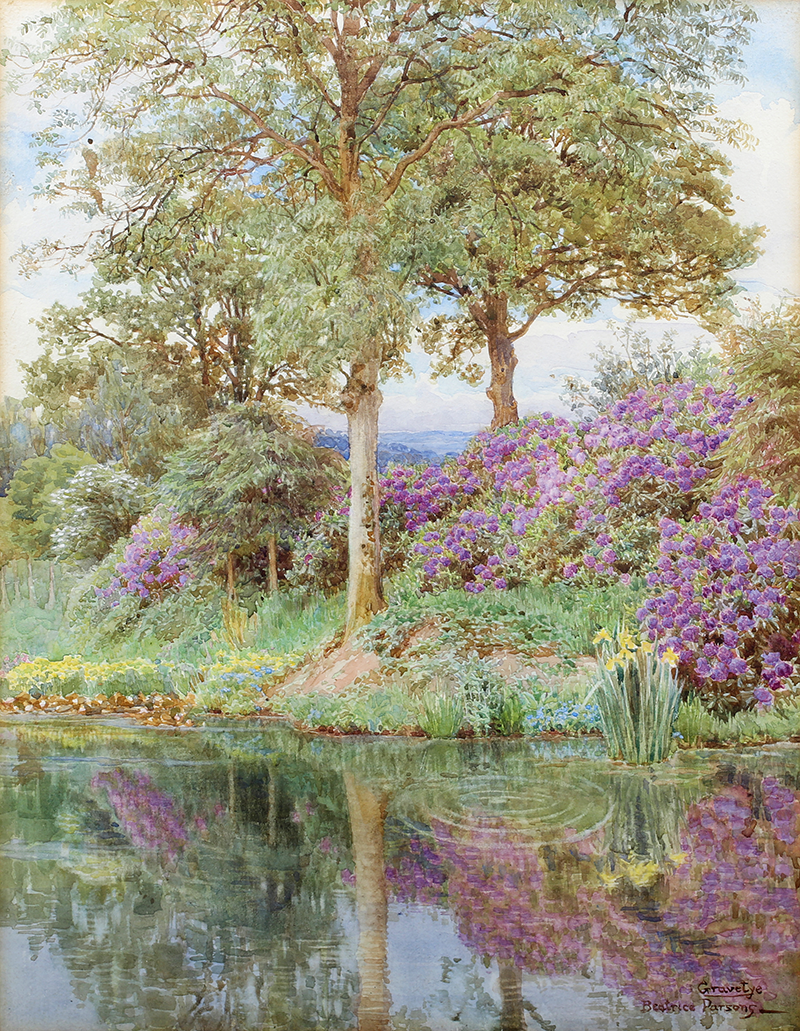

Beatrice Emma Parsons (1869-1955) was invited to paint the delicate early 20th century watercolour of the Water-Garden at Gravetye Manor in West Sussex by the garden’s designer and patron, William Robinson. He began to create the gardens in 1885. From humble beginnings in Ireland Robinson made his fortune as a garden writer. Amongst his most influential books were The Wild Garden and The English Flower Garden. Today he is best known for his understanding of the wild garden, a garden which celebrates nature rather than controlling it. He introduced the modern mixed border and popularised things we take for granted today like secateurs and hosepipes. Beatrice Parson’s was famous for her paintings of gardens in full colour. Her depiction of the rhododendrons reflecting in Gravetye’s lake is beautifully conceived. It realised £1000 at Toovey’s.

Rudyard Kipling opened his poem The Glory of the Garden with this verse – ‘Our England is a garden that is full of stately views, Of borders, beds and shrubberies and lawns and avenues…’

The English love affair with the garden remains as strong today as it has always been.