An exciting exhibition at Pallant House Gallery has just opened titled Leon Underwood: Figure and Rhythm. The show gifts us with the first museum retrospective exhibition of Leon Underwood’s work. It explores the artist’s treatment of the human figure from delicate portrait etchings to sculptures, expressing rhythm and movement.

This insightful show has been curated by Pallant House Gallery’s Artistic Director, Simon Martin.

Underwood would often follow an independent path. Influenced by his deep spirituality and understanding of place in the procession of human history. Underwood’s work celebrates the vitality of ancient civilisations and tribal art. Unusually for such a talented artist there is not a readily apparent common voice uniting the different phases of his work. However, the exhibition reveals the influences in each stage of the artist’s evolution and makes apparent the repeated rhythms and Underwood’s connectedness with the artists and artistic movements of his time.

He taught at the Royal College of Art and subsequently at his Brook Green School in his Hampstead studio. He at once influenced his pupils and was influenced by them. Amongst Leon Underwood’s most gifted pupils were the artists Gertrude Hermes, Eileen Agar and Henry Moore.

Simon Martin notes Leon Underwood’s unorthodox approach to drawing, emphasising ‘individuality, and the need to convey volume, mass and direction with great economy.’ The sculptor, Henry Moore, was to praise Underwood’s ‘passionate attitude towards drawing from life. He set out to teach the science of drawing, of expressing solid form on flat surface and not photographic copying of tone values, nor the art school limitations of style in drawing’.

During the First World War Underwood served as a camouflage artist and the influence of this on his work is highlighted in the exhibition.

Underwood had begun to collect tribal art in 1919. Inspired by tribal art’s vitality and directness of expression the artist created directly carved embryonic shapes like the beautifully formed ‘Untitled (Foetus)’ from 1924 in chalk.

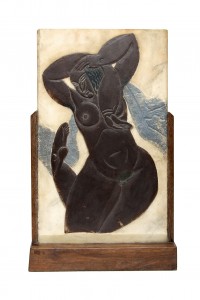

Many of the early sculptures are shallow reliefs like the rhythm of an erotic dance depicted in ‘The Dance of Salome’ carved in marble in 1924.

Simon Martin suggests that Underwood’s sculptures from the 1920s and 30s have a link with the pioneering pre-war work of leading sculptors like Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill; as well as the direct carvings of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. This is certainly apparent to my eye.

In 1923 wood engraving was introduced at the Brook Green School. Out of the innovative environment created by Underwood a school of wood engraving emerged which would lead to the formation of the English Wood Engraving Society in 1925. The sculptures and wood engravings from this period are for me amongst the most exceptional pieces in the exhibition.

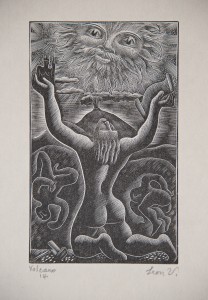

This restless and searching artist travelled to Mexico in 1929. The Aztec and Mayan sites that he visited would inspire mythical pictures. Take for example the wood engraving ‘Volcano’. Here a naked man kneels his arms raised in a gesture of praise with the Volcano beyond. In his hands he holds aloft a sculpture and a piece of paper, his sculpting tools lie at his knees, perhaps symbolic of artistic creativity. Beside him are two figures. The one to the left is drawing an outline of himself. It is as though they have been incised into the very fabric of the earth.

The ambitious canvas ‘Chaac-Mool’s Destiny’ was painted in 1929. It courageously explores the transformative power of cultural objects in museums and these objects are depicted in the British Museum. This image would certainly have resonated with Underwood’s former student, Henry Moore.

There is much more to delight in this retrospective.

The threads and relationships which unite artists and influences within the 20th century Modern British Art Movement are revealed anew in this rich exhibition.

Leon Underwood: Figure and Rhythm runs until 14th June 2015 at Pallant House Gallery, 9 North Pallant, Chichester, PO19 1TJ. For more information go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557. The accompanying book ‘Leon Underwood: Figure and Rhythm’, edited by Simon Martin, provides a wonderful insight into this lost artist whose life and work brings together so many threads of the Modern British Art Movement in the 20th Century. Priced at £19.95 it is available from the Pallant House Bookshop.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 11th March 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.

All images © The Estate of the Artist and The Redfern Gallery, London.