I have been thinking about St George, the patron saint of England, whose life is celebrated this week, and I was reminded of the frescoes at St Botolph’s, Hardham. These beautiful wall paintings include a series of panels devoted to St George. The simple church with its exterior lime washed walls lies just to the south of Pulborough. It is one of my favourite places to stop and pray when I am working.

The first time you encounter the medieval frescoes of one the five Lewes Group of Churches, you cannot fail to be moved by the clarity and beauty of these late 11th/early 12th century wall paintings. The frescoes at St John the Baptist, Clayton, St Botolph’s, Hardham, and Coombes at Lancing are still visible and alive in their predominantly russet hews. They were first termed the Lewes Group in the early 20th century, reflecting a consensus of academic opinion that these pictures reflected a school of monastic artists from the powerful Cluniac Priory of St Pancras at Lewes.

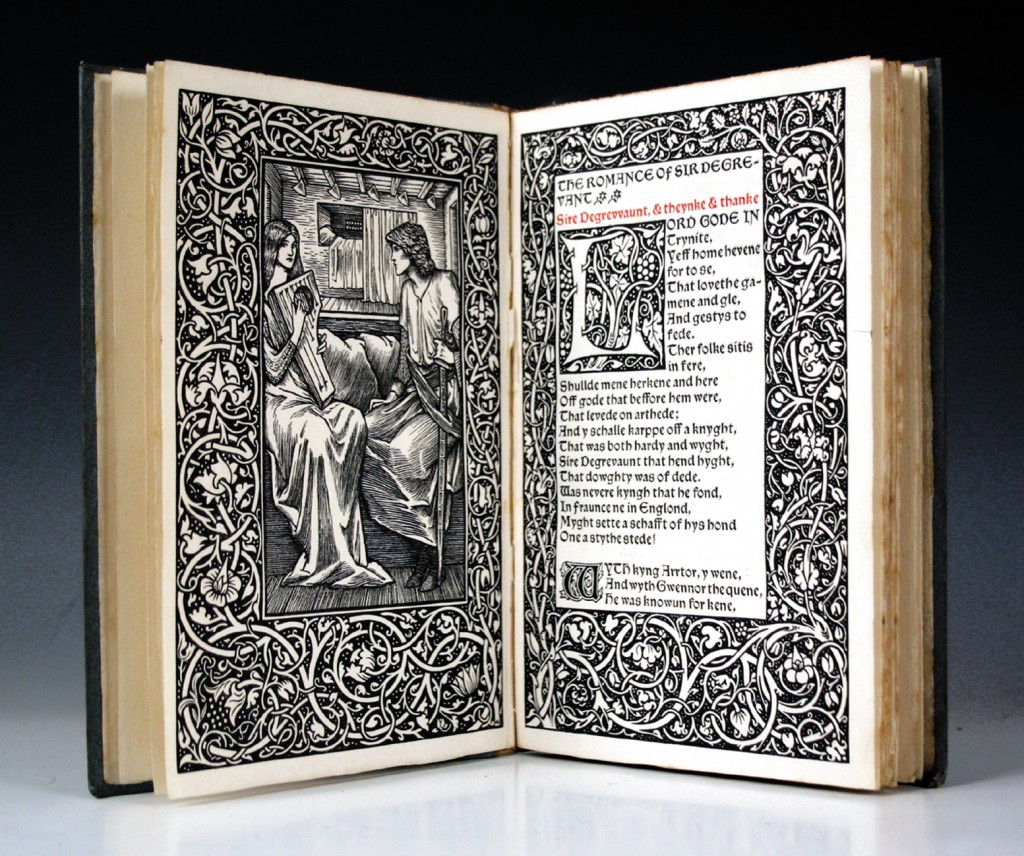

The style of these wall paintings is influenced by both the Byzantine and the Romanesque. The Byzantine Empire developed out of the Roman and they never forgot their classical heritage in respect of art and architecture. There was, however, a conscious movement towards the more abstract and less representational with elongated stylized figures. It was as though the artists were seeking to allow us to see beyond our immediate perception – to glimpse the glory of God and inspire us to devotion.

Frescoes are wall paintings painted directly on to the plaster while it is still wet. The artist has to work quickly and as the plaster dries the pigments and image are fixed. This technique was used throughout the Renaissance in Italy and elsewhere.

While the work at Hardham is less refined than the painting at Clayton, it is equally engaging, embodying the clarity and directness which defines the Lewes painters. Some of the figures at St Botolph’s reflect the Romanesque figures of the French Tradition. Take, for example, the famous depiction of Adam and Eve with their elongated bodies and small heads. It is these characteristics which set them apart from earlier paintings. But at Hardham there is play and movement in the drapery of the clothes, which, to my eye, highlights the characteristics and influence of the earlier Anglo Saxons in the painter’s hand.

This was certainly the considered view expressed by patron and art critic Clive Bell when he wrote about the medieval church frescoes at Clayton and Hardham for the Miller’s Press, Lewes, in 1947. Clive Bell’s opinions on art were influential. He championed Picasso and was married to the artist Vanessa Bell of Bloomsbury and Charleston House fame. Using the methods of contemporary art criticism, he disputed whether all the Lewes Group paintings were united in their stylistic qualities and influences. He did not, however, question the artists’ association with the Cluniac Priory at Lewes.

When you arrive at St Botolph’s, sit and rest a while. Open your heart to a millennium of layered love, prayer and worship. Allow your eyes to adjust. Take time to stop and stare and, as you do, you become aware of the extraordinary frescoes painted in those russet hews so typical of the Lewis group of Churches to which Hardham belongs.

Since the Renaissance we have become used to viewing art in frames. While the work may invite us in, we nevertheless remain the viewer. The painted medieval church is different; here we inhabit the piece of art, joined with the narratives displayed all around us.

In viewing art, the qualities of the aesthetic and the religious are held in tension. Where there is a shared religious heritage, visual art can inspire a vital, living religious experience. They can, however, be viewed purely as a process of rational thinking, a form of teaching, at once experiential and contemplative. Above the chancel arch at Hardham, for example, Jesus is depicted as the sacrificial Lamb of God (the Agnus Dei). In the chancel, the painting of Adam and Eve seeks to allow us to comprehend our free will as creatures created in the image of the God, who knows us completely, delights in us and invites us to accept His love.

On the lower tier of the north wall, you will discover a series of depictions of St George. In the first section he is on horseback bearing a lance. It was originally thought that this depicted our 4th century patron saint slaying the dragon. Little is known of his life but it is thought that he was a Christian Roman soldier, who defended his fellow believers against persecution and was martyred for his actions. In the 1960s it was discovered that the dragon was in fact a slain figure with a kite-shaped shield. It is now thought that this scene relates to descriptions of the Battle of St Antioch in 1098. The battle was part of the First Crusade. Accounts of the battle describe how a later St George and two other saints, mounted on white horses and bearing white banners, came to the relief of the crusaders. Further scenes at Hardham show him being held captive, tortured and martyred on the wheel. It is remarkable to reflect that these pictures were painted shortly after the Battle of Antioch.

These stories reflect the courage and bravery offered by these soldier saints in defending the people they served. Their examples of selfless love and service to others is as resonant today as it was then as our armed forces seek to bring peace, to make lives better through their courage and sacrifice, wherever they serve around the world.

St Botolph’s, Hardham, is open daily with regular Sunday services.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 24th April 2013 in the West Sussex Gazette.