As September progresses, we look to the change of seasons and we have been blessed by a last and precious glimpse of summer before autumn comes. Many of us will be out in our gardens this weekend preparing for autumn, pruning back shrubs and tidying borders. As the ground lies fallow, the structure and design of our gardens holds its own delights. At the heart of these designs architectural features are often to be found: jardinières, sundials and pots. In the late nineteenth and early part of the twentieth centuries a very British expression was given to the Art Nouveau through the Arts and Crafts movement.

Among the leading exponents of the Arts and Crafts taste was Liberty & Co. Its founder, Arthur Lasenby Liberty, built the Liberty brand by employing some of the country’s leading designers, though he insisted that they work anonymously. One of these designers was Archibald Knox, who joined Liberty & Co in 1899. Knox was the creative force behind Liberty’s Celtic Cymric and Tudric designs, worked in silver and pewter. In addition to metalwork and jewellery, Knox designed terracotta garden ornaments, carpets, wallpaper and fabrics for Liberty & Co, displaying virtuosity across all of these disciplines.

Another notable designer of garden pottery in the Celtic style was Mary Seton Watts. In 1900 she founded The Compton Potters’ Arts Guild. Inspired by the thinking of John Ruskin and William Morris, the Guild sought to celebrate and enable craftsmen through their creative handiwork. Mary’s Compton Pottery quickly became a successful business and it continued to prosper until 1955. The Arts and Crafts gallery, designed specifically to house the work of her husband, George Frederic Watts, was designed by Christopher Turnor and opened in 1904. It also served as a hostel for Mary Seton Watts’ potters. The Watts Gallery in Compton, Surrey, remains open to visitors today and, as well as exhibiting examples of G.F. Watts’ art, it houses over two hundred examples of Compton pottery.

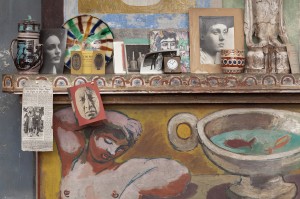

My first single-owner collection and country house sale at Toovey’s was held at Little Thakeham, the exquisite Arts and Crafts home designed by the renowned architect Sir Edwin Lutyens in 1902. The contents of the sale reflected the exceptional eye, particular taste and sensitivity to the stylistic quality and period of this important house of its then custodians, my late friend Tim Ractliff and his wife Pauline. Tim and Pauline loved the house and its gardens, preserving and sharing their home as one of the country’s leading country house hotels. Once sold, Little Thakeham retired again from the public gaze and it remains a very private family home.

The garden effects in the auction included the Liberty & Co pottery jardinière illustrated here, which was designed by Archibald Knox. It added focus to the formal garden. The bowl and stem were typically decorated in relief with a Celtic knot design. Today a jardinière of this quality and design would potentially realise in excess of £5000. The lavender-filled pot also shown is a famous Compton design and one which is still reproduced today. Displaying Mary Seton Watts’ use of Art Nouveau design is the terracotta sundial. Although at the time there was no record of this design being from the Compton Pottery, it can be attributed to Compton by comparing the decorative motif on its stem with a similar one used on a known birdbath from the pottery. Today, an example like this would carry a pre-auction estimate of £3000-5000.

We British remain pots about pots, as illustrated by their values. They provide form and focus to a garden. Charming examples can be bought for a few hundred pounds, while the finest collectors’ pieces achieve thousands at auction. As you tidy your garden for the onset of autumn and winter, perhaps take time to stop and stare and imagine if a pot might work for you!

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 11th September 2013 in the West Sussex Gazette.