The celebrated Royal Academy print maker and watercolourist, Norman Ackroyd, is the subject of a retrospective exhibition titled Wild Isles at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. The show coincides with the RA250 celebrations.

Norman Ackroyd., CBE, RA, immerses himself in the wilderness of the landscape to paint and etch, creating intensely atmospheric work in the romantic tradition.

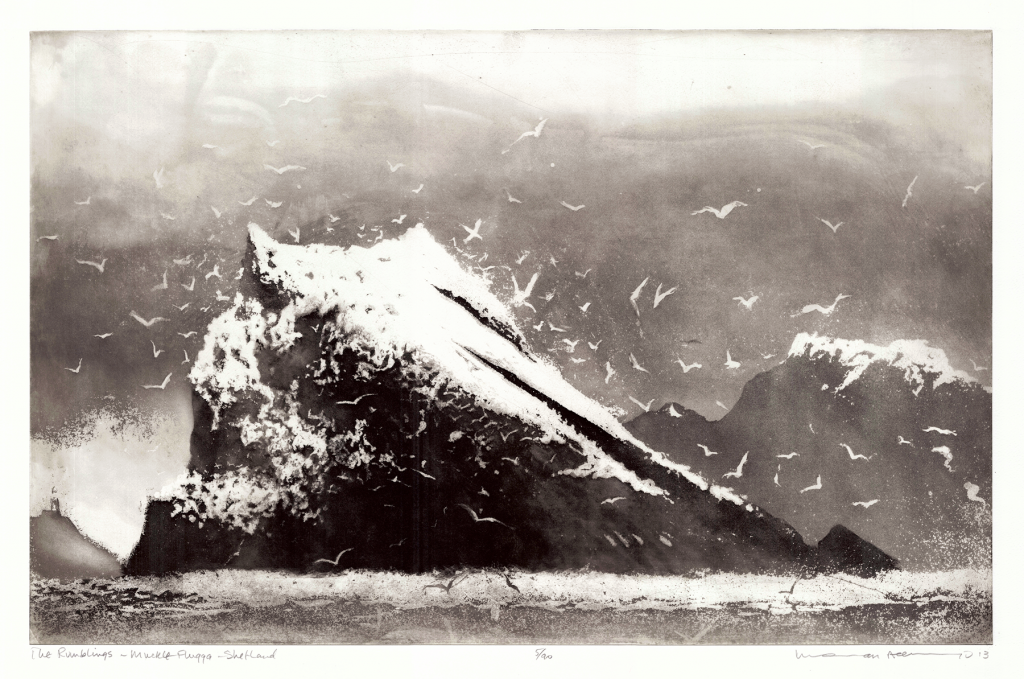

Norman Ackroyd has been attracting much attention in this his eightieth year. Speaking with the writer Robert Macfarlane on BBC Radio 4’s outstanding Only Artists series Ackroyd describes how he has focused on the landscape and especially the West Coast of Britain. His prints are representational. Using his visual and aural memory together with sketches made en plein air Ackroyd says “…I just get the atmosphere and feeling of how I felt then…that’s the image, and it’s an image which can’t be described…it’s like trying to catch a butterfly and it comes from memory…What I hope for most when I’m painting is for all my rational thoughts to disappear: my eye, heart and hand become connected, and then I can distil the real essence of the landscape.’

Norman Ackroyd works in aquatint. It was John Piper’s book Brighton Aquatints which was credited with the revival of this print technique in the 20th century.

The process of creating an aquatint involves exposing a plate, usually of copper or zinc, to acid through an applied layer of granulated, melted resin. The acid incises the plate between the granules creating areas of evenly pitted surface. This can be varied by applying additional resin, scraping and burnishing. Different strengths of acids are also employed. When the grains are removed and the plate is printed it results in variations of tone. The effect often resembles watercolours and wash drawings, hence the name Aquatint.

His study of the British Isles’ most northernmost point, Muckle Flugga, Shetland, is an image of a fixed place and point in time. The cliff has a real sense of mass. In contrast the birds, sea and sky are alive expressing movement. Ackroyd has said “…an etching is not the black ink, it’s the white paper you leave – it’s the reverse.”

In contrast On Twyford Down, Deacon Hill captures the softer southern hills outside Winchester, though still with a sense of drama.

Rooted in the English tradition Norman Ackroyd’s work often relates to a place – a landscape. He brings a particular quality of engagement to his subjects, capturing the poetic, his emotional response and thoughts, as well as the essence of the physical reality.

‘Wild Isles’ runs until the 24th February 2019 and thanks to the generosity of sponsors, DeLonghi, admission to the exhibition is free. The exhibition can be seen at Pallant House Gallery, 9 North Pallant, Chichester, PO19 1TJ. For more information go to www.pallant.org.uk.

By Rupert Toovey, a senior director of Toovey’s, the leading fine art auction house in West Sussex, based on the A24 at Washington. Originally published in the West Sussex Gazette.