In celebration of the Arts and Crafts Movement Toovey’s will be holding a specialist auction of Arts and Crafts Furniture & Works of Art on Tuesday 8th September 2015.

The Great Exhibition of 1851, housed in Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace at Hyde Park, celebrated industry, manufacturing and industrial design. In reaction to the industrial age the Arts and Crafts Movement sought to improve standards of decorative design and revive handicrafts. It stood against the automatic processes involved in mass-production and its social impact. Inspired by the writings of Augustus Pugin, John Ruskin and William Morris, Arts and Crafts design was often based upon a re-interpretation of the Medieval, sometimes incorporating the Celtic with a very English interpretation of the Art Nouveau.

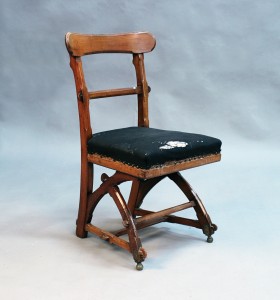

The specialist in charge of this Arts and Crafts sale is William Rowsell. I am excited to discover a walnut chair designed by Pugin already consigned for the auction. William says “Pugin worked as an architect and designer. He was a passionate advocate of the Gothic Revival style which he famously applied to the House of Commons. You can see the influence of the Gothic in the stretchers and mouldings of this chair.” In the 1830s and 1840s Pugin published books on furniture decoration as well as architecture. William continues “Most of Pugin’s furniture was made for the houses which he designed.” This remarkable chair carries an estimate of £300-500.

My eye is taken by a Liberty & Co Tudric mantel timepiece. Liberty was owned and run by Sir Arthur Lasenby, a leading figure in the English Art Nouveau movement. In 1903 a new type of pewter emerged which Liberty called Tudric. It contained a high proportion of silver in the alloy. Tudric objects were made by the firm William Hair Haseler in Birmingham. William Rowsell smiles enthusiastically as he says “These Tudric designs re-interpret the Celtic style incorporating the Art Nouveau as well. The use of blue and turquoise enamel cabochons, like on the dial of this clock, is outstanding.” Tudric pieces of this quality are prized by collectors and William explains that this is reflected in the presale estimate of £2000-3000.

Also entered for auction are the pair of early 20th century Leeds Fireclay Company Lefco ware stoneware jardinières which would grace any garden with their Art Nouveau naturalistic decoration. They carry an estimate of £600-900.

To my eye the English Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts Movement combines beauty and purpose. It was considered progressive in its own time but the influences of the simple pre-industrial cottage can be noted.

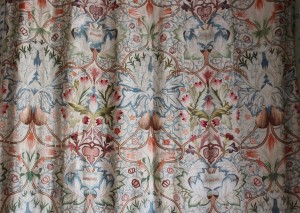

The simplicity of an Arts and Crafts interior entered into, and influenced, the spirit of much 20th century design. Nevertheless these interiors were comfortable and gathering. The clean architectural lines of Arts and Crafts furniture and works of art were complimented by the use of rich colours in the fabrics, enamels, glazed ceramics, silver and glass. The quality of design speaks to our contemporary tastes.

Entries for Toovey’s specialist auction of Arts and Crafts Furniture and Works of Art on Tuesday 8th September 2015 are currently being invited. William Rowsell will be delighted to offer free advice on your Arts and Crafts furniture and objects whether you are considering selling or buying. Telephone Toovey’s on 01903 891955 to arrange an appointment.

Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 3rd June 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.