John Duncan Fergusson (1874-1961) is known as one of the four ‘Scottish Colourists’, along with F.C.B. Cadell, G.L. Hunter and S.J. Peploe. Fergusson’s career, however, was much more international than those of his peers. He spent much of his adult life in France and England, which explains his association with the European modern art world and its influence on his work. He has been described as one of the leading figures of Celtic Modernism. In common with his fellow Scottish Colourists, Fergusson painted still lifes, landscapes and interiors, but he was always drawn to the female form.

Living in Paris between 1907 and 1913, Fergusson found himself at the centre of the birth of modern Western art. It was while he was in Paris that he made his name.

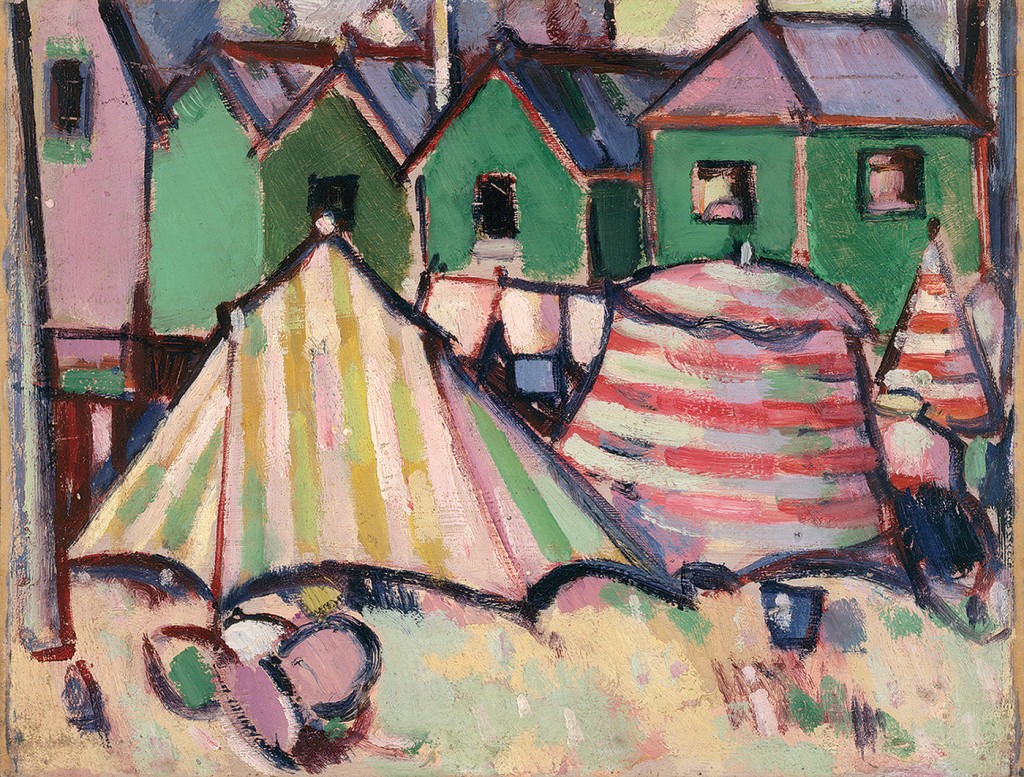

The restrained quality of his work from this period is in sympathy with the new Fauve approach. Fauvism describes a group of early twentieth century artists, including Henri Matisse and André Derain, who emphasised strong colour and painterly qualities over representationalism and Impressionism, as shown in ‘Bathing Boxes and Tents at St Palais’, painted in 1910.

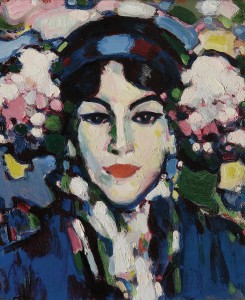

The Fauvist simplicity of his blocked-in colour gives Fergusson’s art a more Expressionist edge. Take, for example, ‘Hortensia’, painted in 1910. The subtle composition gifts this painting with informality and the black edging finely balances the figure. His paintings increasingly recorded a response to a particular place, a moment, and as they did so, they became more vibrant and decorative.

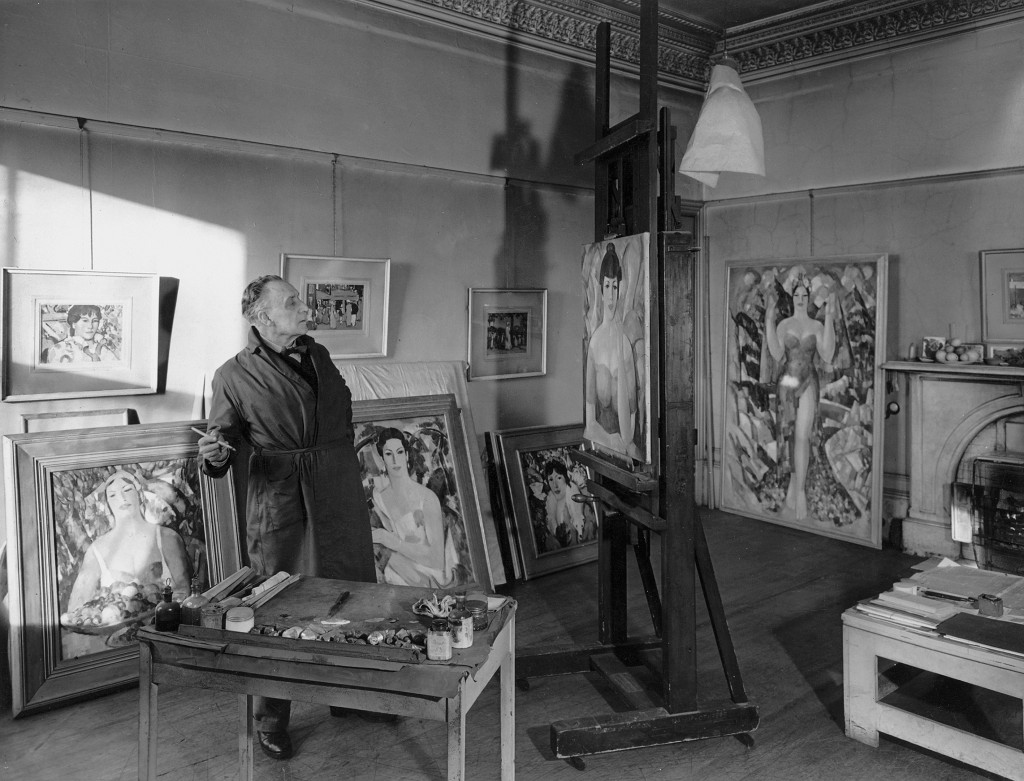

The 1930s begun triumphantly for Fergusson when ‘Déesse de la Rivière’ was purchased for the French National Collection. But with the outbreak of war in in 1939, he and his lifelong partner, Margaret Morris, moved to Glasgow. They had met each other in Paris in 1913. The photograph shows Fergusson in his studio in Glasgow in the 1950s; in the corner you can see ‘Danu, Mother of the Gods’. Fergusson often painted stylised visions paying homage to his Celtic roots, like this work from 1952. Here Danu, the mother goddess worshipped by the first Celtic tribes to invade Ireland, is depicted in dramatic pose. The handling of paint, colour and strong composition is typical of this artist’s hand.

Fergusson and Morris co-founded the New Art Club and the New Scottish Group. These exhibiting and discussion societies were at the heart of the arts revival in Glasgow at the time. Fergusson remained a generous man and went to great lengths to help other artists and promote modern art. His generosity is apparent in his work.

J.D. Fergusson’s paintings, with their dazzling palette and dramatic handling of subjects, still capture and delight the viewer’s attention. It is a rare treat to see such a body of work exhibited outside Scotland. The exhibition runs until 19th October 2014. For more information go to www.pallant.org.uk.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 6th August 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.