Nature has often provided the inspiration and components of our most effective and radical medicines, even in our modern scientific age.

Rembert Dodoens (1517-1585) is often described as the father of botany.

From the 1530s Europe’s fascination with natural history grew leading to a botanical Renaissance.

In Tudor times herbs were used for their culinary, medicinal and strewing properties. Herbs would be strewn on the floors and surfaces of homes to deter insects and to disinfect, as well as for their fragrant qualities. From Medieval times, and no doubt before, herbs were associated with medicine, including in the monastic tradition

Rembert Dodoens was born Rembert Van Joenckema in Mechelen in 1517. At the time Mechelen was part of the Spanish Netherlands. Dodoens worked and travelled widely in Europe returning to his hometown in 1538 where he served as the town physician.

A physician and botanist, Dodoens’ beautifully illustrated Cruydeboeck (plant book) was first published in 1554. Dodoens divided the plant kingdom into six categories based on their properties. The work was published in the vernacular rather than Latin which heightened its popularity. In its various editions it became the most important botanical work of the late 16th century and the most translated book after the Bible.

In particular it dealt in detail with the medicinal properties of herbs. Many at that time would have seen it as a pharmacopoeia identifying plant-based compound medicines.

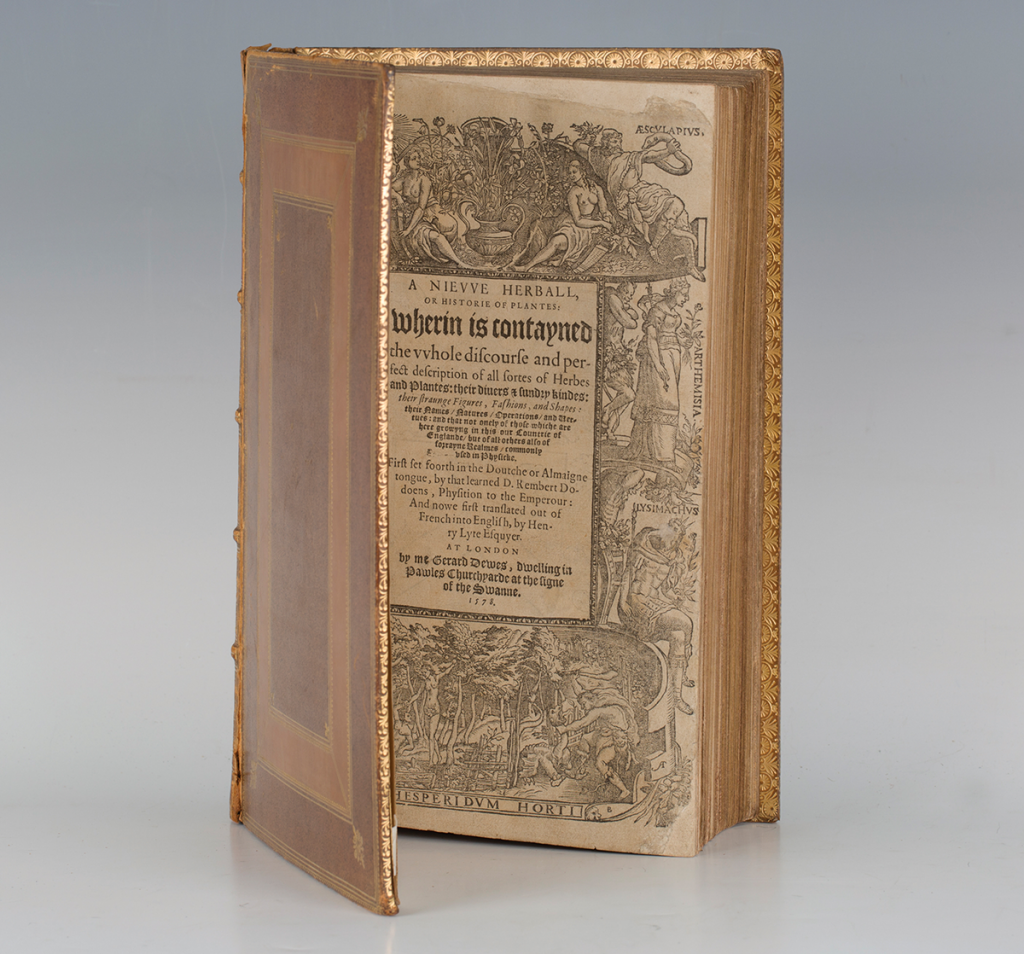

Dodoens’ Cruydeboeck was translated into English by the botanist and antiquary Henry Lyte (c.1529-1607) during Elizabeth I’s reign. Published under the title ‘A Nievve Herball, or Historie of Plantes: wherein is contained the whole discourse and perfect description of all sorts of Herbes and Plantes: their divers and sundry kindes, their strange Figures, Fashions, and Shapes…’ in 1578, the English version became a standard work and remained in use for some 200 years.

The early English translation illustrated, bound in later, early 20th century panelled calf binding, dates from 1578 and realised £3000 at Toovey’s.

In 1572 the Dutch population rose up against the Spanish occupation. Dodoens’ house was looted and burned. His reputation was such that the King of Spain, Philip II (1527-1598) invited him to become his personal physician. Dodoens instead chose to serve the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II (1527 1576) and his successor Rudolf II (1552-1612) as physician.

In 1582 Dodoens returned to the Netherlands where he took up the post of Professor of Medicine at the University of Leiden until he died in 1585.

Today we continue to explore the extraordinary possibilities of cures for diseases from and inspired by the natural world. There is still so much we do not understand more than 450 years after Dodoens wrote his Cruydeboeck. I hope the nations of the world will come together to protect the precious resource of the world’s forests and plants before they, their wonders and their blessings are lost to us.