Thanks to the generosity of Mr Edwin Davies CBE, who gave his outstanding collection of Japanese Cloisonné enamels to the V&A, Horsham Museum & Art Gallery are going to display some of the finest, most jewel-like objects ever made. It was Davies’ vision that a selection of items should tour the country and with the help of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, it is being made a reality. Horsham District Council’s Horsham Museum & Art Gallery is one of just ten venues nationwide that will be able to display these masterpieces of Japanese art and craft. The exhibition Japanese Treasures: Cloisonné enamels from the V&A opens on 15 June and runs until 22 September.

The exhibition highlights the ability of a country in turmoil to create artistic masterpieces through the 61 objects on display at the museum. For the golden age of the craft was the era portrayed in the 2003 film The Last Samurai, when Japan’s old feudal society rapidly transformed itself. The craftsmen who made the celebrated Samurai armour and weapons were metaphorically not beating swords into ploughshares, but into exquisite enamels. Some of their patrons, the Samurai class, became acknowledged masters of this new craft, reflecting the degree that the society was changing.

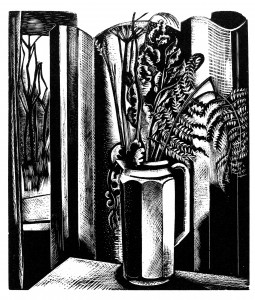

Over a century ago, as this revelatory exhibition shows, the Japanese were perfecting enamelling, the art of wire in-fills, of creating deeper colours, of polishing to a higher gloss the finished surface and then making objects that appealed to the west. Enamel vases are decorated with Japanese images known to appeal to the western aesthetic: peonies, chrysanthemums, swallows, carp, dragons and butterflies are featured against a range of deep colours. Each item is like a treasure and so unsurprisingly whilst in the west we link the name to a manufacturing process, the cloisonné, in Japan, is linked to the ‘Seven Treasures’ mentioned in Buddhists texts.

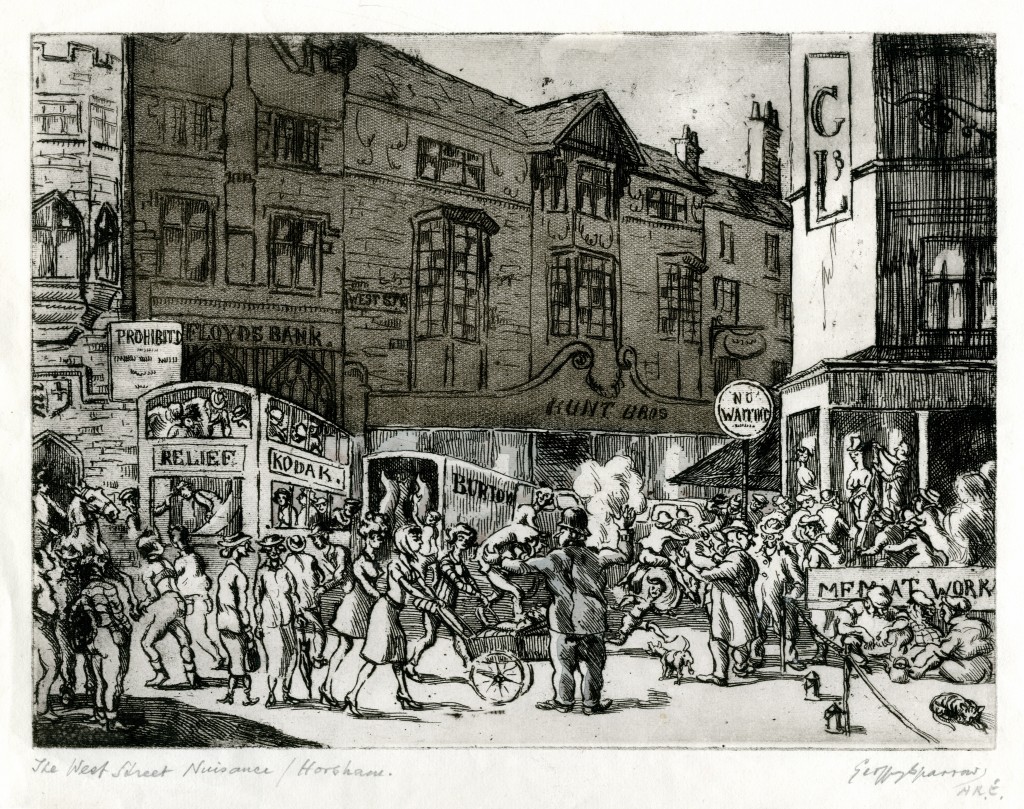

Horsham, an ancient market town noted for its stone roofs in the heart of Sussex, may seem a strange venue to host such an exhibition. Yet at the very same time the Japanese were creating these highly sophisticated superbly designed masterpieces residents of the town were visiting the remote lands. Robert Henderson and his wife Emma, who lived at Sedgwick Park, toured Japan, as the old order was being subsumed in a dash to modernise. They brought back photographs of the people and places to remind them, some of these will be on display. The exhibition itself would not have been possible without the good will and support of the local community including the auction house Toovey’s.

Edwin Davies CBE, OBE is one of the V&A’s most generous benefactors and has been a trustee of the Museum since 2007. Until 2006, he was Chairman of Strix, a leading manufacturer of electronic heating controls for kettles and other water-heating appliances. The company won many prestigious export and innovation awards and Davies was awarded an OBE in 2000 for services to industry and a CBE in 2012. A prominent philanthropist, he has supported a wide range of institutions.

The Victoria and Albert Museum, is the world’s greatest museum of art and design. It has been collecting Japanese Cloisonné enamels since 1867.