A rather wonderful exhibition has just opened at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester which explores the place of the Still Life in the procession of British art with a particular emphasis on the 20th century and the contemporary. The Still Life was introduced to England in the 17th century by the Dutch. Ever since artists have used the genre to explore and experiment.

The show is arranged chronologically with works from the 17th century to the present day and cleverly traces the progression of British art from realism and post-impressionism through the major art movements of the 20th and 21st centuries. In the first room Ethel Walker’s ravishing Flower Piece No.4 keeps company with paintings by Ivon Hitchens, Harold Gilman, the Scottish Colourists and a delicate interior scene by the Sussex artist Eric Ravilious titled Ironbridge Interior. I’ve often reflected that an English Country House interior is made up of a series of Still Lifes formed of eclectic, arranged objects, art and furniture. Here Ravilious paints the restrained interior with his customary use of light. The hatching, shadows, tone and colour on the chair, wall and flower filled jug lending life to the stillness of this scene. The composition cleverly creates a layered perspective leading the viewer’s eye through the room to the window and landscape beyond.

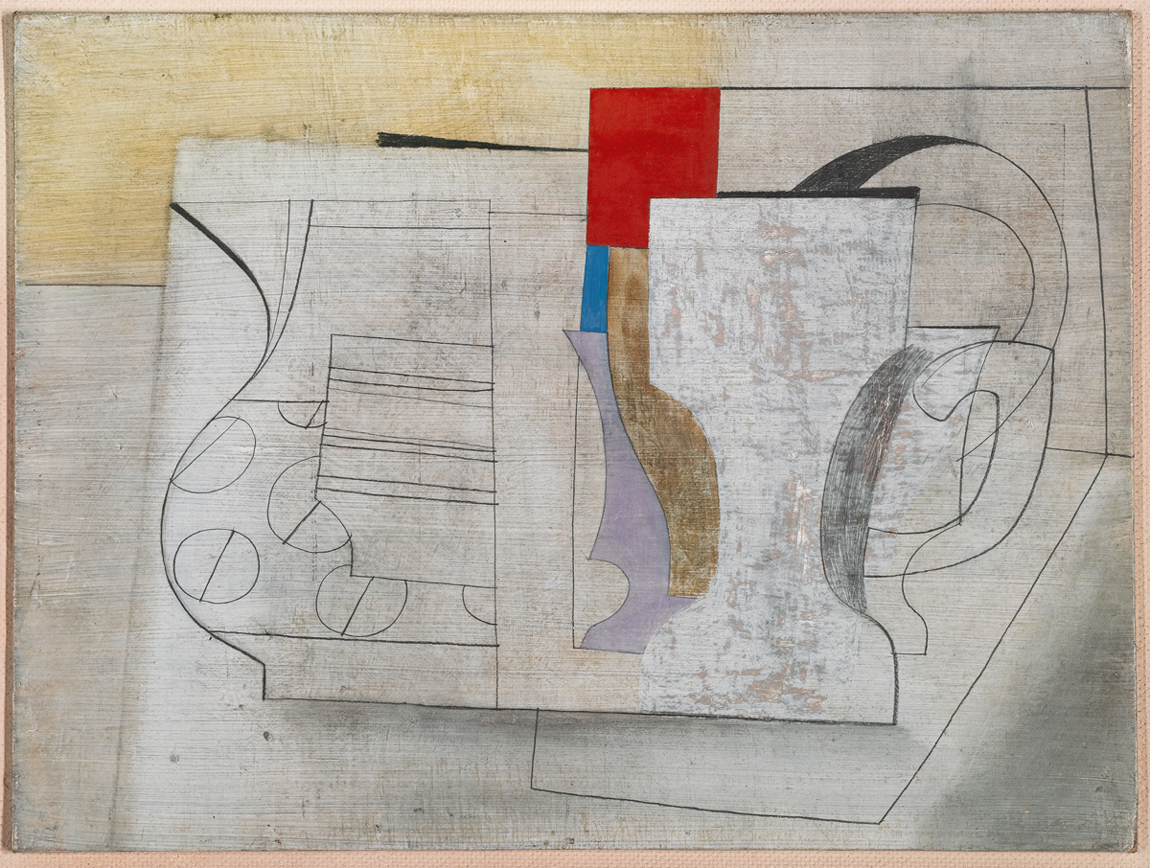

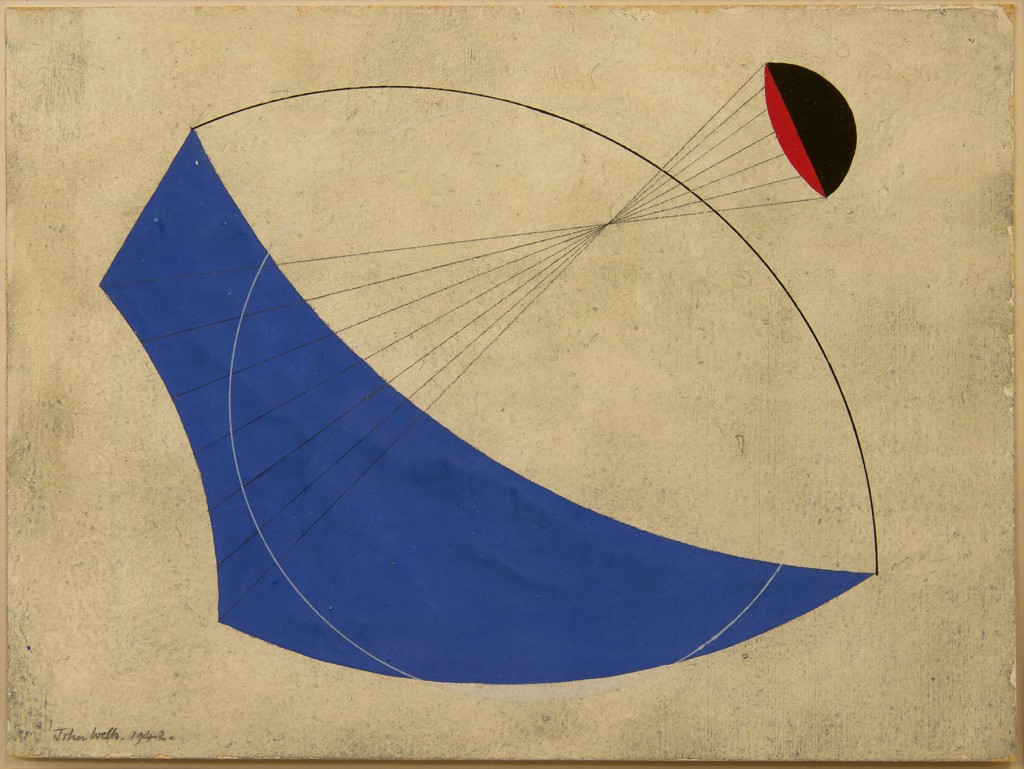

Ben Nicholson’s beautiful Still Life, St Ives, Cornwall, painted in 1943-45, depicts a large white mug on a curtained windowsill which, like Ravilious’ interior, draws the eye to the landscape through the window where toy-like, traditional fishing boats nestle against the backdrop of sea and sky. The Union Jack wouldn’t look out of place on a seaside sandcastle. There is an innocence to the scene which contrasts with the experience of war. 17th century Still Lifes are often filled with allegory. The Nazis considered modernist art to be degenerate so the painting’s modernism is an allegory in itself which provides a very British, understated voice speaking eloquently and powerfully of peace and innocence in reaction to the violence of Nazism.

Director of Pallant House Gallery, Simon Martin, has described this season’s series of exhibitions as “…an artistic journey that transcends time and borders and invites you to explore the intersections of tradition and innovation.”

This exhibition shows us how the genre of Still Life has constantly evolved reflecting our changing society and the themes of love, loss, beauty, decay and consumerism. The Shape of Things: Still Life in Britain is a stunning exhibition, eloquent and beautiful. You really must see it.