A pair of Chinese famille rose enamelled porcelain tea caddies dating from the Qing dynasty have just sold at Toovey’s Fine Art Auctioneers for £132,000. They were being displayed on a window sill in a Sussex home when they caught the eye of a Toovey’s valuer during a routine visit. The result illustrates the strength of Chinese Hong Kong collectors and the benefits of the post-Brexit pound which have caused prices and competition from abroad to soar.

Today’s Chinese collectors are following in the tradition of the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799) who was the last of the great imperial art collectors and patrons in Chinese history. His genuine passion for art and collecting seems to have been inspired by his grandfather, the Kangxi emperor (1654-1722), and his uncle Yinxi (1711-1758).

The Qianlong emperor was prolific in his collecting applying an exceptional personal connoisseurship not only to the acquisition of art and antiquities but also to his patronage. His collection would number more than a million objects. It included the collection of the Ming emperors (1368-1644) which was the oldest art collection in the world with a continuous collecting tradition dating back over 1600 years.

The Qianlong emperor took a personal interest in porcelain production and was an ardent collector of it. Many of the types of porcelain associated with the Qianlong emperor, however, were seeded under the Emperor Yongzheng’s supervisor of the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen, Tang Ying (1682-1756).

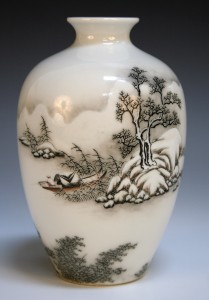

Toovey’s Asian art specialist, Tom Rowsell, explains “The mid-18th century porcelain designers had an unprecedented freedom due to their technical understanding of glazes. This resulted in enamelled wares often decorated with dense, complex and colourful designs as you can see on the side panels of this remarkable pair of Qianlong period tea caddies from the imperial kilns. Their shape and proportion is typically well judged and shows the influence of European taste, the superb fine white bodies and beautifully ordered and executed decoration are quintessentially of the period.”

I comment on the virtuosity in the contrast between the restrained depiction of the blossoming branches and flowering stems which enfold the finely executed text, and the polychrome enamelled sides densely filled with lotus flowers and scrolling tendrils on the yellow and iron red grounds. Tom agrees and says “This technical excellence and style is explained by the production processes refined by Tang Ying at Jingdezhen. Tang Ting was the foremost ceramic expert in China. He was summoned to Beijing in 1743 to illustrate and catalogue the imperial collection and described the process of porcelain manufacture in twenty steps. This led to an elaborate division of labour at the imperial kilns so that no one person was responsible for the production of a single piece at Jingdezhen.”

Today’s Chinese collectors are as passionate in their collecting as their imperial forebears and the market shows no signs of abating. If you would like advice on your Chinese objects Tom Rowsell can be contacted on 01903 891955 or by emailing auctions@tooveys.com.

By Rupert Toovey, a senior director of Toovey’s, the leading fine art auction house in West Sussex, based on the A24 at Washington. Originally published in the West Sussex Gazette.