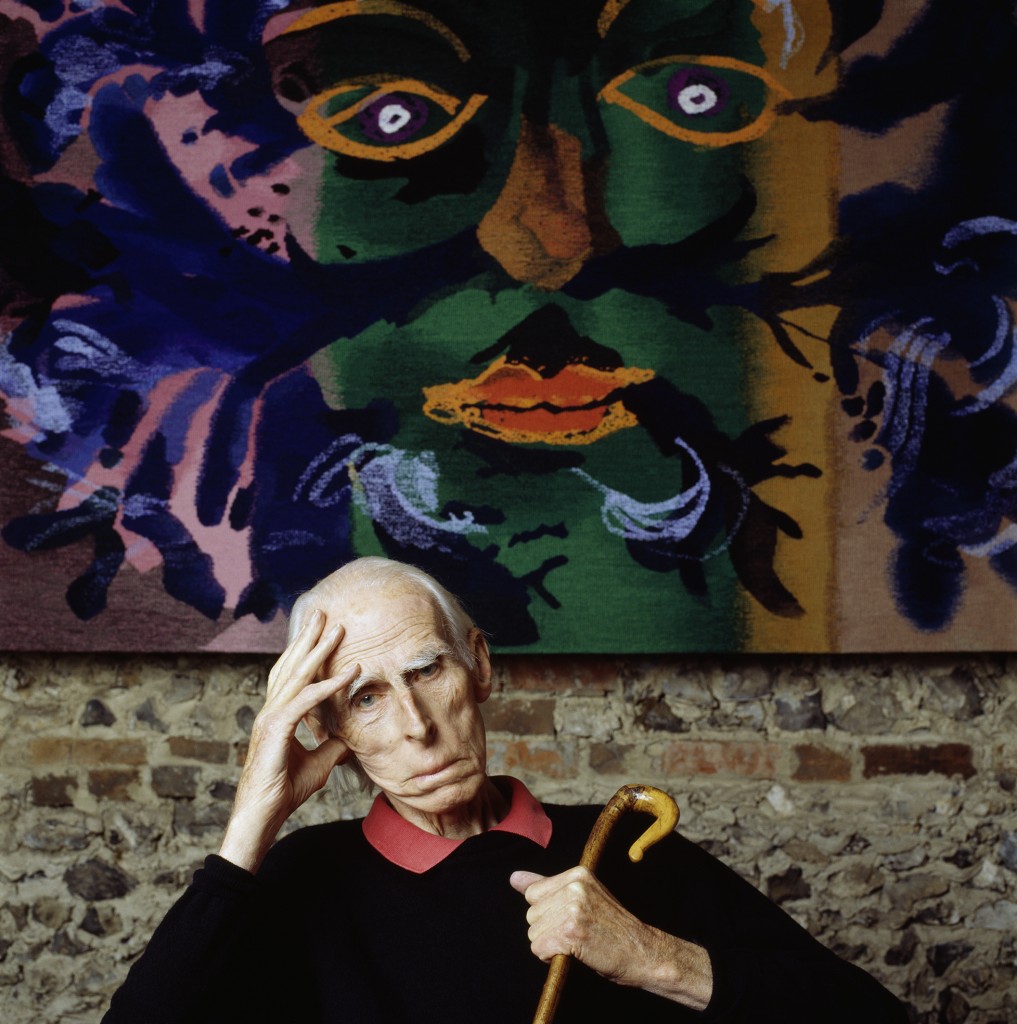

A remarkable exhibition ‘John Piper: The Fabric of Modernism’ has just opened at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. It marks the fiftieth anniversary of the installation of John Piper’s Chichester Cathedral reredos tapestry.

This is the first major exhibition to explore John Piper’s textile designs. It highlights the influence of Piper’s paintings and drawings on his designs. There is much to feast your eyes on. Paintings are displayed alongside designs and textiles illustrating how he reworked his themes and interests in various media. He worked in the abstract, romantic and classical traditions as a painter, designer, writer, printmaker and ceramicist. Whilst there is something of the modern in all his work he is, nevertheless, rooted in the tradition of individual voices in British Art. The exhibition highlights the central and recurring themes in Piper’s work which include religious imagery, historic architecture and the abstract.

In the 20th century two industrialized world wars had forged a shared experience of suffering and conflict in Britain. It fell to artists and their patrons to give voice to this new national consciousness in a period of political, social and religious change. John Piper’s work is deeply bound up with this story.

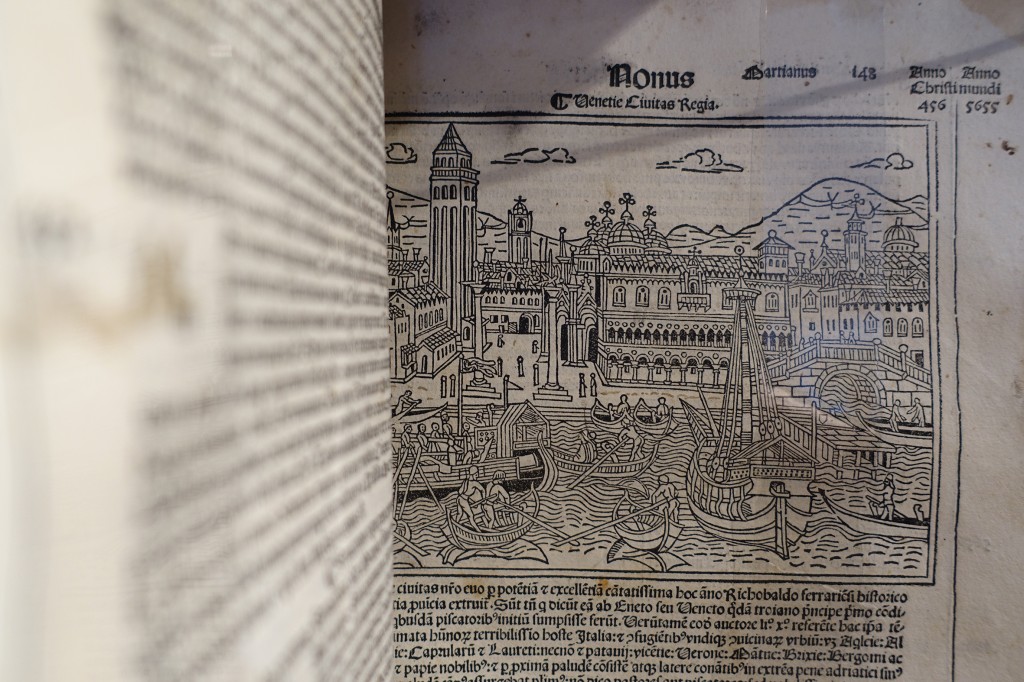

Walter Hussey was Dean of Chichester Cathedral and famous for his patronage of the arts through the church. In his book ‘Patron of Art’ Hussey notes how he chose to follow Henry Moore’s advice to commission John Piper to create a worthy setting for the High Altar. With his great sympathy for old churches he suggested a tapestry. Tapestry, he argued, would work in concert with the old stonework and 16th Century carved oak screen. He felt that the seven strips of tapestry would be able to be read as a whole across the narrow wooden buttresses of the screen with its crest of medieval canopies.

In the January of 1965 Piper presented a final sketch. The artist’s familiarity with the language of abstraction remains evident. It met with favourable opinion. But at lunch with Hussey and others, Piper was deeply troubled when the Archdeacon of Chichester commented that there was no specific symbol for God the Father in the central section of the design. The lack of this symbol in the earlier design by John Piper, illustrated here, is notable. After much consideration Piper introduced the white light to the left of centre on the tapestry itself. The tapestry panels are schematic in their use of symbolism. The Trinity is represented in the three central panels. God the Father is depicted by a white light, God the Son by the blue Tau Cross and the Holy Spirit as a flame-like wing, all united by a red equilateral triangle within a border of green scattered flames. The flanking panels depict the Gospel Evangelists St Matthew (a winged man), St Mark (a winged lion), St Luke (a winged ox), and St John (a winged eagle); beneath the Elements earth, air, fire and water.

As we journey through Holy Week and mark Jesus’ death upon the cross on Good Friday the Tau Cross seems particularly poignant with its symbolic wounds on each spar. Jesus’ role in creation from before the beginning of all things to the triumph of his death and resurrection are powerfully proclaimed in this extraordinary tapestry.

John Piper set himself to the task of designing the tapestry panels. He employed subtle changes in the colour of threads to avoid jagged edges. Piper was convinced that Pinton Frères, in the small French town of Felletin, near Aubusson, was the right atelier of weavers to produce the tapestry. The weavers worked with a true and faithful sense of the artist’s intentions and hopes for this design. Their painstaking, lengthy discipline in producing these panels gift the work with contrasting qualities of life, movement and spontainaity. The subtleties and life in the tapestry are best observed in natural light. The tapestry was installed fifty years ago in the autumn of 1966.

I am excited that Toovey’s Fine Art Auctioneers are sponsoring ‘John Piper: The Fabric of Modernism’ at Pallant House Gallery, 9 North Pallant, Chichester, PO19 1TJ. The exhibition runs until 12th June 2016.

What a wonderful Easter treat – Pallant House Gallery and Chichester Cathedral!

For more information on current exhibitions, events and opening times go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557. For details of Holy Week and Easter services at Chichester Cathedral visit www.chichestercathedral.org.uk.

By Rupert Toovey, a senior director of Toovey’s, the leading fine art auction house in West Sussex, based on the A24 at Washington. Originally published in the West Sussex Gazette.