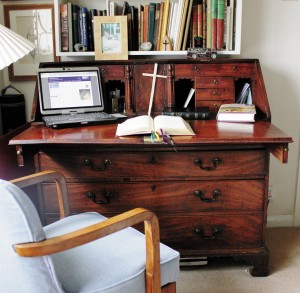

Two hundred and ninety Lots of Antique and Period Furniture will be offered at Toovey’s auction on Friday 25th April. Starting the sale is Lot 2001, a Victorian burr walnut and mahogany campaign secrétaire chest with recessed brass handles and mounts. This wonderful quality item bears the inset maker’s label marked ‘Hill & Millard, 7 Duncannon St. London. Patentees’ and is fitted with two short and four long drawers, the secrétaire drawer with leather writing surface, hidden compartments and letter rack, raised on later fitted squat feet. Height approx 104cm, width approx 100cm.

Hill & Millard were recorded in London commercial directories from the mid-19th Century as ‘military outfitters and trunk makers,’ describing themselves in advertisements as ‘Manufacturers of Portable Military Furniture.’ The firm are regarded by many as one of the best manufacturers of campaign furniture in this period.

“Campaign furniture was produced at a time when military personnel were required to provide their own furniture for tours of duty,” says Toovey’s furniture expert, Will Rowsell, who continues “the furniture needed to be robust for travel, and compact to fit within small cabins, tents, or if they were lucky, a billet. It is quite unusual to find an example with the luxurious burr walnut drawer fronts, perhaps indicating this was once the property of a wealthy military gentleman of high rank – we will never know for certain, and we can only speculate as to what action this lovely piece of furniture might have seen.”

“Campaign furniture was produced at a time when military personnel were required to provide their own furniture for tours of duty,” says Toovey’s furniture expert, Will Rowsell, who continues “the furniture needed to be robust for travel, and compact to fit within small cabins, tents, or if they were lucky, a billet. It is quite unusual to find an example with the luxurious burr walnut drawer fronts, perhaps indicating this was once the property of a wealthy military gentleman of high rank – we will never know for certain, and we can only speculate as to what action this lovely piece of furniture might have seen.”

Because of its compact size and clean lines, campaign furniture fits within the modern home. This secrétaire chest carries a pre-sale estimate of £2000-3000 reflecting its quality. It will be offered for sale at 10am on Friday 25th April at Toovey’s Spring Gardens rooms.