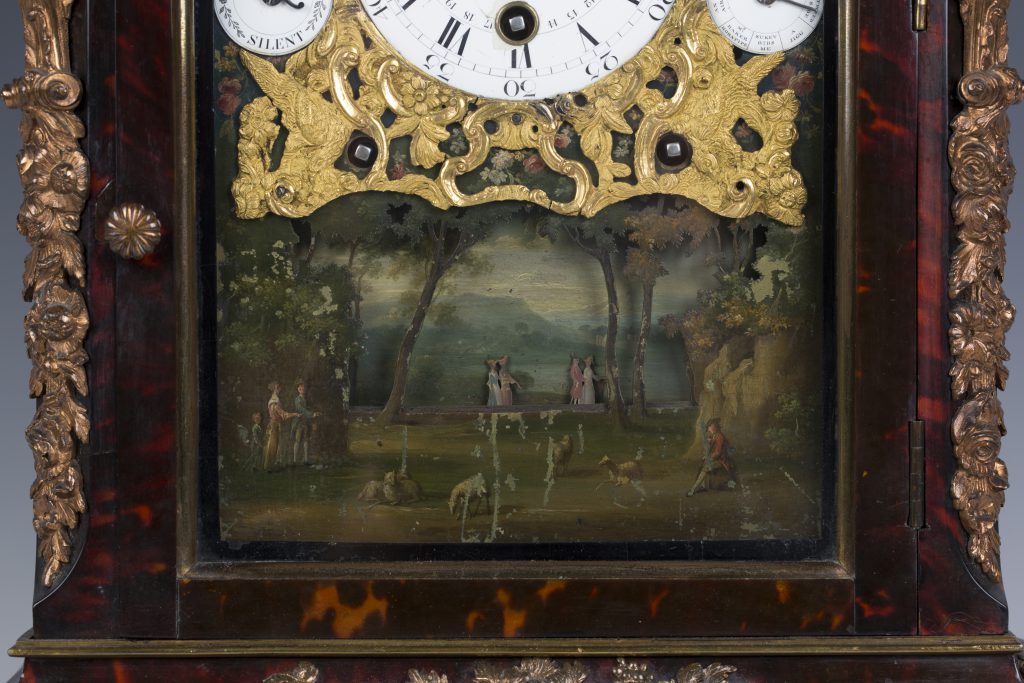

A rare late 18th century tortoiseshell and gilt-metal bracket clock with a processional automaton by the celebrated British entrepreneur and goldsmith James Cox (1723-1800) has been discovered by Toovey’s specialist, Tom Rowsell, in a London collection.

From the mid-18th century James Cox ran a company specialising in the manufacture of objects de vertu which were intended to delight and surprise his clients. He became famous for his extravagant clocks with their ingenious automata which made objects move, seemingly of their own volition. The clocks were hugely expensive and were sold across Europe and as far afield as India, China and Russia. Cox employed craftsmen from across Europe to create these extraordinary pieces.

Tom explains that this James Cox automaton clock was part of the estate of a London collector. It was the only clock in the collection which was predominately focused on Chinese porcelain. A late example of James Cox’s work, the clock dates from the late 18th century and has a complicated three train movement with automaton, playing ten tunes on fourteen bells. The automaton on this clock sees figures and animals process from left to right. His clocks are still a source of wonder and were never intended to be practical. Indeed they have been referred to as ‘magical moving objects’.

That a British clock like this should appeal to a connoisseur of Chinese porcelain should not be a cause of surprise. The Chinese Emperor Qianlong (1735-1795) collected both Western and Chinese clocks and two of James Cox’s chariot clocks dating from 1765 and 1766 can still be seen in The Palace Museum in the Forbidden City, Beijing.

Although Cox had an early Indian connection most of his business was with China via Canton. A number of exotic, valuable pieces were exported there from 1763. These mechanical objects were received with great curiosity by the Chinese court and must have made Cox substantial profits. Trade seems to have developed steadily but by 1770 the market had reached saturation. The demise of Chinese interest deprived Cox of this his most profitable and important market.

In response to the decline in the eastern markets for his clocks, James Cox opened a museum in London and charged the public to see his amazing clocks. The manner of their sale in 1775 by national lottery was as ingenious as the objects’ mechanisms. Two of the largest and most complicated of these clocks were the Silver Swan and the Peacock Clock which can be seen at the Bowes Museum at Barnard Castle, Co Durham, and at the Hermitage, St Petersburg, Russia.

Producing such magnificent objects was hugely costly and brought with it significant financial risks. James Cox would face bankruptcy on more than one occasion.

This rare James Cox automaton clock will be auctioned in Toovey’s next curated sale of fine clocks and watches on Thursday 1st November 2018 and is estimated at £15,000-£25,000. If you would like advice on your clocks telephone 01903 891955 or email auctions@tooveys.com.

By Rupert Toovey, a senior director of Toovey’s, the leading fine art auction house in West Sussex, based on the A24 at Washington. Originally published in the West Sussex Gazette.