People often remark how exciting it must be for me as a fine art auctioneer to discover wonderful things which have lain undiscovered – it is and it happens more frequently than you might expect. It was on a visit to Newhaven, Sussex, early in the New Year when the gales were blowing, that I discover a marvellous collection of sculptures and prints by the important Modern British artist, Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005) which are to be auctioned at Toovey’s on Wednesday 26th March 2014.

The sculptures and prints represented in the sale were given to the current owner over a period of years after he and his family had been befriended by Eduardo. They recount fond memories of visits to Eduardo’s home and studio, of outings and meals together.

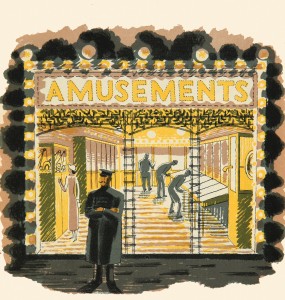

Eduardo Paolozzi claimed to have embraced “…the iconography of the New World. The American magazine represented a catalogue of an exotic society, bountiful and generous, where the event of selling tinned pears was transformed in multi-coloured dreams…” This fascination with American culture is clearly expressed in the plaster maquette of a Sky Scrapper included in the sale and illustrated here. In the late 1940s and early 1950s a cold-war generation of artists in Britain began to turn towards New York for inspiration rather than Paris. Paolozzi had a foot firmly in both camps. He emerges as an artistic bridge between post-war Europe, Britain and the US.

One of Paolozzi’s most celebrated sculptures is ‘Newton after Blake’ made for the forecourt of the British Library. It was commissioned by its architect the late Colin St John Wilson, who was also responsible for the Pallant House Gallery extension in Chichester, which houses many works from the architect’s own collection. The collection on sale includes several bas reliefs depicting ‘Newton after Blake’. Eduardo Paolozzi was fascinated by the artist William Blake’s image of Sir Isaac Newton from 1795. In Blake’s depiction the scientist appears oblivious to all around him, consumed by the need to redact the universe to mathematical proportion. Paolozzi explained of his own sculpture that “…Newton sits on nature, using it as a base for his work. His back is bent in work, not submission, and his figure echoes the shape of rock and coral. He is part of nature.”

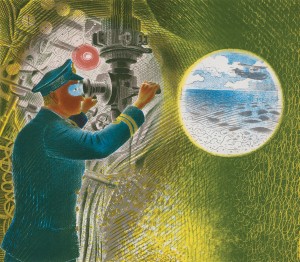

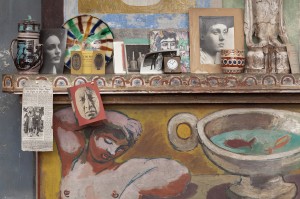

Alongside Paolozzi’s cultural icons and totems the resilience and fragility of the human person and the influence of humankind’s relationship with technology expressed through the culture of science fiction and robots also recur as themes in his work. The complicated array of influences are often collaged into a single work. Take for example the two heads illustrated which are defined by the geometric shapes from which they are formed. The smaller plaster bust ‘Computer Head’ references technology’s effect on our consciousness. The larger bust ‘Head’ is an example of the busts which Paolozzi described as an amalgam of African art, geometric art which speaks of the machine in our age, and the influence of boogie woogie. A rich collage which, for him, described modernism.

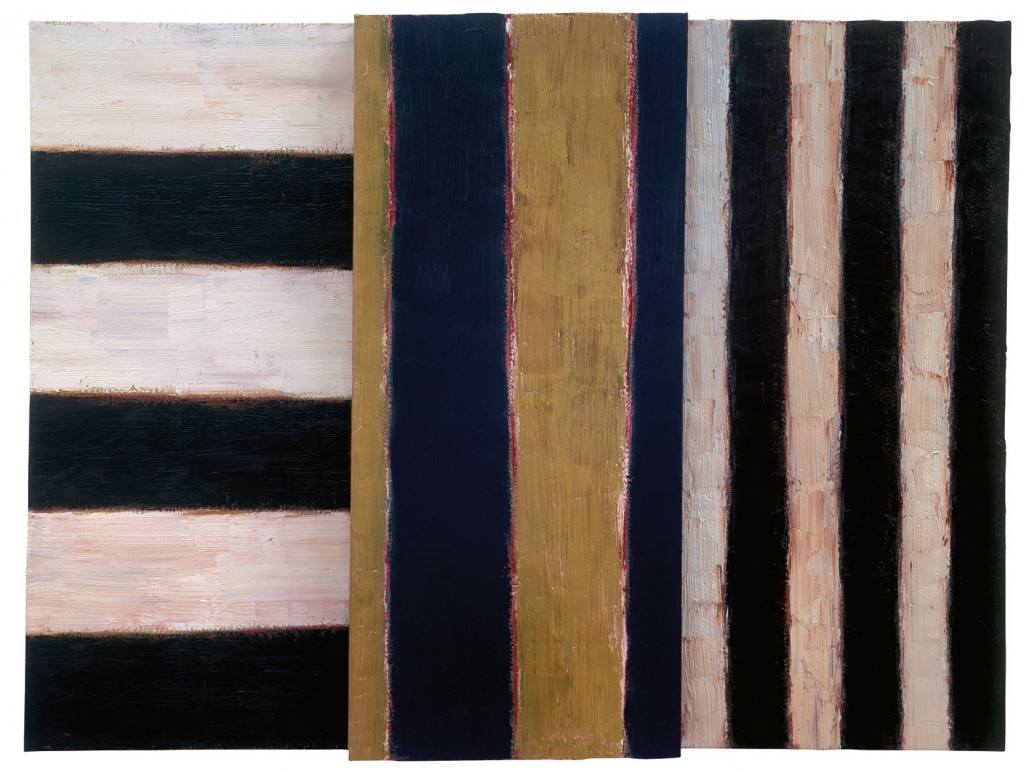

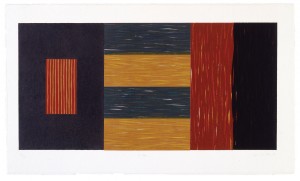

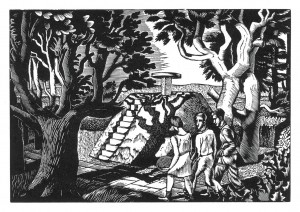

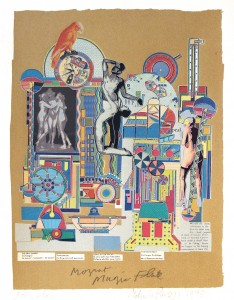

Paolozzi’s prints give voice to the idea of relationship between collage and image making. The prints with their often vibrant colour allowed the artist to explore the theme of finding visual comparisons between music and drawing. They are also connected with Paolozzi’s sculptural reliefs.

This exciting collection provides a valuable insight into the work of Eduardo Paolozzi. There are iconic examples and more modest pieces describing his delight and humour in the world, often with a surrealist influence. Paolozzi’s work is layered, textural and thought provoking delighting the eye and the mind. The sale exhibition provides a wonderful opportunity to see this famous artist’s work and to acquire an example for your own collection. It is on view from Saturday 22nd March 2014 and will be auctioned on the morning of Wednesday 26th March 2014. Further details of opening times and images are available on tooveys.com. Catalogues are available from Toovey’s offices or by telephoning 01903 891955.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 19th March 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.