In the September of 1848 the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in London. Its principal members included the young painters John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Dante Gabrielle Rossetti (1822-1882), and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910).

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century had destroyed the rich tradition and iconography of Medieval and Renaissance Christian art in Britain. The young artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were aware that their contemporary culture lacked a strong tradition of religious art.

They found themselves in sympathy with the Oxford Movement which was led by High Church members of the Church of England. Amidst some controversy it brought symbolism and vestments back into worship, and some Roman Catholic practices were re-introduced.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood set out to place Christian subjects at the heart of their paintings. These pictures were not, however, intended solely for churches, but rather for public exhibition or private contemplation. Their expression of holiness breaking out into the world and into the everyday is something which has a particular resonance for myself and my calling.

From its very beginnings Pre-Raphaelitism was characterised by an innovative style in reaction to the conventions of the Royal Academy. Indeed, Rossetti joined the Royal Academy School in 1844 but left, bored by the curriculum which he felt allowed little room for the imagination.

The Pre-Raphaelites adopted a way of painting on a wet, white ground, imitating the ancient technique of fresco painting. Although slow and difficult it gifted their colours with brilliance and luminosity.

They employed intense detail and depicted the natural likenesses of individual men and women as they sought to bring authenticity to their work. They often painted the landscape backgrounds of their pictures in the open air. It was whilst painting outdoors that John Everett Millais and his follower, Charles Allston Collins (1828-1873), met Thomas Combe. Combe had made a fortune printing Bibles for the University Press and he used his wealth in acts of philanthropy and in patronising these artists. Today his collection forms the basis of the Ashmolean Museum’s group of Pre-Raphaelite work.

The Brotherhood’s work was savagely attacked in the press when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1850 and 1851. The famous Victorian critic and artist, John Ruskin, wrote a letter in their defence to The Times in May 1851, saying that the Pre-Raphaelites ‘…will draw either what they see, or what they suppose might have been the actual facts of the scene they desire to represent, irrespective of any conventional rules of picture-making’.

William Holman Hunt’s ‘A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the persecution of the Druids’ was amongst those pictures strongly criticised in 1850. The painting portrays an act of mercy as a converted British Christian family hides a missionary wearing a red chasuble from the Druids. Beyond the depiction of a particular imagined scene the painting is filled with Christian symbolism. The converts hold a thorn branch, sponge and grapes, symbols of Christ’s death upon the cross and of Holy Communion. The bowl of water speaks of Baptism and the net refers to Jesus’ instruction to his Disciples to be fishers of men. Hunt depicts the humanizing effects of Christianity.

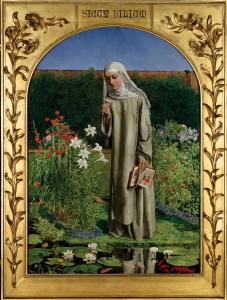

The flowers in Charles Allston Collins’ ‘Convent Thoughts’ were painted in the garden of Thomas Combe. The nun in this enclosed garden contemplates a passion flower, an allegory of the Crucifixion. The book she holds open has depictions of Christ on the Cross, and the Annunciation, both painted from actual manuscripts. The lilies in the garden and on the frame symbolise the qualities of the Virgin Mary’s virtue. In all this the magnificence of sacrifice is portrayed.

Both paintings were owned by Thomas Combe.

Combe also owned a version by William Holman Hunt of ‘The Light of the World’, which he gifted to Keble College, Oxford. It can still be seen in the college chapel. This has been described as ‘a pivotal work’ in Hunt’s career and was perhaps the most famous Victorian painting in its time. The inspiration for the picture is said to have come to Hunt whilst he was reading the Book of Revelation in the Bible. The verse which caused this religious epiphany was “Behold’ I stand at the door, and knock: if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me.” The version shown here is from a stained glass window designed by Hunt, at All Hallows, Tillington, Sussex. The light of Christ is depicted by the lamp which illumines his regal figure. The door has no handle; as Jesus offers invitation to us we are to respond with invitation to him. It is vital to our meeting with Christ.

All Hallows, Tillington is under the care of the Revd. Bob Mitchell. Its wonderful array of stained glass windows inspire prayer and reflection. Bob and his congregation will be celebrating Harvest Festival at their family service this coming Sunday, 4th October 2015 at 11.15am. You are invited to join them. Bring some produce, groceries or a donation, and be inspired by ‘The Light of the World’.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 30th September 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.