This week I am once again at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester for ‘Sickert in Dieppe’ which runs until 4th October 2015. This exemplary exhibition explores the formational relationship that Walter Sickert (1860-1942) had with the French seaside resort of Dieppe.

Walter Sickert was a leading and influential figure in the Modern British Art Movement. The exhibition is the inspiration of Pallant House Gallery Curator, Katy Norris. In her introduction to ‘Sickert in Dieppe’ she writes ‘Walter Sickert’s enduring fascination with the popular Normandy resort of Dieppe represents a remarkable aspect of his career.’

For me this is a relevant and contemporary exhibition. Although Sickert’s paintings show us the life and scenes of Dieppe some hundred years ago, the vibrant seaside town he depicts is still recognizable to us today. We can feel the heat and shade of his pictures and pick out many of the same landmarks. The ambient sounds and life of the town that he captures speak to us across the years.

From his childhood, and for more than forty years, Sickert would return to Dieppe. The exhibition highlights the formative influence this vibrant seaside town had on the artist, and the extraordinary breadth of subjects he engaged with. He would produce a comprehensive topographical account of the town, its people and its environs.

The work chosen for this show illustrates how Sickert’s work was influenced by his acquaintance with the French artist Edgar Degas and his closeness to Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro.

Encouraged by Degas Sickert started to emphasise what Katy Norris characterizes as ‘the everyday realism of his subjects…his paintings became more representational, based upon rigorously planned squared-up drawings and featuring strongly delineated architectural patterns.’ Influenced by Degas’ work Sickert broadened his range of subject matter to include the race course and circus scenes. The latter provided the forerunners to paintings like ‘Brighton Pierrots’ and his London music hall scenes.

Painted in 1894, ‘L’Hotel Royal, Dieppe’ depicts what appears to be a public festival. The tricolour flags flutter in the coastal breeze. The figures and sea front hotel are depicted beneath the dramatic sky, turned purple by the light of the setting sun.

Sickert left his first wife Ellen Cobden and settled with the local fisherwoman, Augustine Villain, in the suburb of Neuville. From here the narrow roads of the fishing community linked the Arcades de la Poissonnerie with the harbour and prosperous parts of Dieppe. These adjacent and contrasting architectural spaces fascinated Sickert. Take for example ‘The Façade of St Jacques’ painted in 1902. The bright palette and thickly worked paint shows some of the characteristic of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting but, unlike them, he did not work ‘en plein air’.

In 1912 Sickert married Christine Angus Drummond. They made their home at the Villa d’Aumale in the valley of Eaulne, just ten miles from Dieppe. Katy points out that it was during this period that the artist developed his particular method of ‘applying the pigment in a patchwork of flattened layers of colour’.

Sickert was cut off from Dieppe by the advent of the First World War.

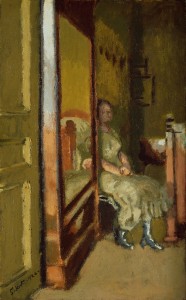

In the October of 1920 Christine lost her battle with tuberculosis and died. Sickert was overwhelmed by grief. In 1921 he took a flat on the seafront at Dieppe. There he painted a series of pictures that he described as ‘figure subjects’. He posed different models in a poorly lit bedroom in his flat. There is a voyeuristic quality to ‘L’Armoire à Glace’ afforded by the composition. Separated by the doorway there is a lack of compassion and empathy between the artist and sitter. It has been suggested that a sexual under-current is implied by the empty bed reflected in the mirrored door of the wardrobe as though from a scene in a brothel.

Sickert visited Brighton in 1913 where he made a speech at the opening of the important ‘English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others’ exhibition. Arranged by the Camden Town Group, it included work by him and many of the nation’s leading artists. He visited Brighton in 1914 with his wife and painted ‘Brighton Pierrots’ in 1915. It seems appropriate, therefore, that ‘Sickert in Dieppe’ should be in Sussex at the Pallant House Gallery, 9 North Pallant, Chichester, PO19 1TJ, until 4th October 2015. For more information on ‘Sickert in Dieppe’ and the gallery’s current exhibition program go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557.

It is wonderful to see Katy Norris’ insight and assured vision expressed throughout this beautiful exhibition. I am proud that Toovey’s is among the headline sponsors of this insightful, relevant and contemporary exhibition. It should certainly be on your must see list this summer!

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 5th August 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.