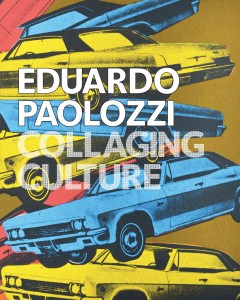

An exhibition of the important British artist Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005) has just opened at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. Its title, “Collaging Culture”, captures the centrality of collage in inspiring and directing the artist’s work across disciplines. But it is the extraordinary breadth of art from the artist’s oeuvre which impresses and provides such insight into his work and times. Paolozzi’s sculptures, printmaking, textiles, ceramics and film are all represented.

Eduardo Paolozzi always located his work within a surrealist context. He claimed to have embraced “the iconography of the New World”. “The American magazine,” he said, “represented a catalogue of an exotic society, bountiful and generous, where the event of selling tinned pears was transformed in multi-coloured dreams.” This fascination with American culture is clearly expressed in his collage “Real Gold” from 1949, illustrated here. Disparate images jostle for the viewer’s attention – a futuristic car, a glamorous woman, tinned orange juice, a couple on a motorbike – and yet in this disunity a narrative for post-war American culture is expressed with a clear artistic voice. Paolozzi acknowledged that defacing an image, erasing and destroying its original context was a metaphor for the creative process itself. For him, raw materials equated with raw images. Simon Martin, Head of Collections and Exhibitions at Pallant House Gallery, explains, “In order to understand Paolozzi and the different aspects of the way he works, not just the sculptures but the prints, textiles and ceramics, you have to recognize the fact that his approach to collage connects all of this.” Paolozzi, the son of two Italian immigrants, worked at the family confectionery shop in the Scottish port of Leith. From an early age he collected cigarette cards and images in scrap albums, many of which he used in later work.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s a cold-war generation of artists in Britain began to turn towards New York for inspiration, rather than Paris. Paolozzi had a foot firmly in both camps and I am interested to better understand this link. Simon enthuses, “Through the process of collage, Paolozzi emerges as an artistic bridge between post-war Europe, Britain and the United States.”

Together with fellow sculptors William Turnbull and Geoffrey Clarke (whose work is represented at Chichester Cathedral and on the chapel of the Bishop Otter campus at the University of Chichester), Paolozzi was inspired by Picasso and Matisse and rebelled against the teaching at the Slade School of Fine Art. A near sell-out exhibition in 1947 at the Mayor Gallery allowed the artist to leave the Slade and go to Paris. There he met and befriended Isabel Lambert. Lambert, herself an artist engaged in drawing figures from the ballet, had modelled for and briefly lived with Alberto Giacometti. It was she who introduced the two artists. The influence of Giacometti is visible in Paolozzi’s sculptures at this time.

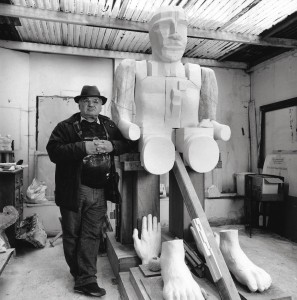

Giacometti provided another rich seam of influence when he introduced Paolozzi to the French existentialist philosopher, writer and political activist Jean-Paul Sartre. Existentialist philosophers disagreed about much but shared the belief that philosophical thinking includes the active, feeling, living human individual and not just the thinking person. Paolozzi’s work was included in the groundbreaking exhibition at the 1952 Venice Biennale of existentialist sculpture in the British Pavilion, alongside sculptors like Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick, Geoffrey Clarke and William Turnbull. In the 1950s Paolozzi was a key member of the Independent Group, which was bound up with the Institute of Contemporary Art. Alongside his cultural icons and totems, the resilience and fragility of the human person and the influence of humankind’s relationship with technology, expressed through the culture of science fiction and robots, also recur as themes in Paolozzi’s work.

A number of British sculptors in the 1960s, like Eduardo Paolozzi and Hubert Dalwood, made work in aluminium. A more contemporary material than bronze, it reflected something of the age of invention and technology in which they lived. Paolozzi said of the large form “Artificial Sun”, circa 1964, that his aim had been to “get away from the idea in sculpture of trying to make a Thing – in a way, going beyond the Thing, and trying to make a presence”. This artificial sun in prefabricated aluminium reflects the artist’s delight in language games. Beside the sculpture in the exhibition is a colour screenprint of the same title from the series “As is When”. Paolozzi produced this series as a reflection on the work of Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein believed that a single proposition could stem from many more complex propositions – something which resonates with Paolozzi’s collage technique.

As a fine art auctioneer in Sussex, I have spent some twenty-nine years journeying with people and sharing the stories of their lives, told through their possessions. I have often reflected that the most precious objects in our lives are those that allow us to tell these stories – the prompts to fond memories. I refer to them as the “patchwork quilts” of our lives. Simon Martin responds, quoting Paolozzi, “All human experience is one big collage,” and he is right. Our human journeys reflect our strengths and our weaknesses, our hopes and our fears, and our joys and our sorrows – layered, at once disparate and united, like a collage – the resilience and fragility of humanity.

Simon Martin has once again produced an exemplary show, which affirms Eduardo Paolozzi’s reputation and place amongst Britain’s leading post-war artists. It is filled with what Simon refers to as “the witty juxtaposition of disparate images”. I hope it will capture and delight your imaginations as it has mine. This revealing and significant exhibition provides a unique insight into this important British artist of the cold-war era and runs until 13th October 2013. The exhibition catalogue, published by Pallant House Gallery and written by Simon Martin, is a must – elucidating on Paolozzi, his work and times. It is available at the Pallant House Bookshop, price £24.95 (special exhibition price £19.95, when visiting the exhibition). For more information and opening times, go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 31st July 2013 in the West Sussex Gazette.