An insightful show of work by the 20th century British artist Paul Nash opened at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester earlier this week, including wood engravings, etchings, photographs, collage and illustrated books.

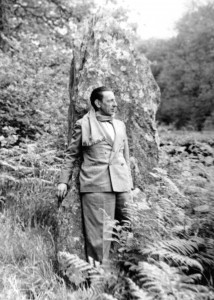

The work provides a rare insight into the relationship between patron and artist, as shown by the photograph taken of Paul Nash by collector Clare Neilson. Their very particular friendship was first formed while Nash was living in and around Rye in the 1930s. It is fitting then that this collection should find its new permanent home in Sussex, thanks to the generosity of Clare Neilson’s godson Jeremy Greenwood and the Art Fund, the national fundraising charity for art.

Simon Martin, Head of Collections at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, is delighted by the gift of the Neilson Collection, which also includes correspondence. “It is a significant addition to Pallant House Gallery’s collection of Modern British Art,” he acknowledged, “and a fascinating and personal view into friendship and artistic patronage in the 1930s and ‘40s.”

Paul Nash is often thought of as an essentially English artist but between the wars he also sought to champion the hope embodied in continental modernism, defending Picasso and experimenting with abstraction before embracing Surrealism. He served as a soldier in the trenches of the Great War and subsequently worked as a war artist on the Western Front between 1917 and 1918 and again during the Second World War. This body of work provides a stark commentary on the reality of war.

He was drawn to objects sculpted by nature and had what some have described as an overriding habit of metaphor. Trees, for example, could take on the character of stones. This serves to highlight the poetic nature of his painting and how firmly rooted he was in the English tradition as well. Indeed, his earlier work is influenced by the 19th century English Romantic tradition of William Blake (who also lived in Sussex, at Felpham, between 1800 and 1803), Samuel Palmer and Dante Gabrielle Rossetti. With this in mind, you could forgive John Piper for including one of Nash’s paintings in his 1943 book ‘British Romantic Artists’. Nash was less than pleased, though. It was the word ‘romantic’ which bothered him and he referred, instead, to the ‘poetic’. Certainly, as an artist he returned again and again to the poetry of the English landscape. He sought to look beyond the immediate to what he referred to as the ‘genius loci’, the spirit of the place, to ‘a reality more real’.

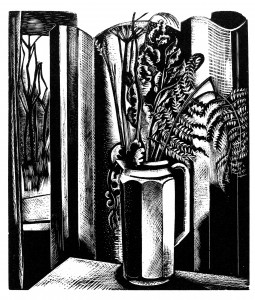

Paul Nash was noted for collecting all manner of objects, including seashells, pebbles, seedpods and bits of branches, all of which fuelled his imagination. In 1920, the Society of Wood Engravers was formed and Nash joined. His still life studies are not generally among his most highly regarded pictures. In this woodblock print from 1927, however, the relationship between the glimpsed landscape and still life reflects a paradoxical quality, which recurs in his work. Note also the uncompromising contrast of black and white, of which some, like Jacob Epstein, were critical. But this technique, combined with his unerring and poetic eye, seeds drama in our imaginations and allows us to glimpse something beyond our immediate perception of the world.

Paul Nash exhibited with Epstein at the important ‘Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others’, where his work was selected by Spencer Gore of the Camden Town Group. The exhibition was held at the Public Art Galleries in Brighton between 16th December 1913 and 14th January 1914. Nash also taught and championed two other artists noted in Sussex, Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden, at the Royal College of Art in London. I have long been of the opinion that Sussex stands out as an important centre for Modern British Artists working in the 20th century. Paul Nash’s original and influential work, his connection with Sussex and the insight the Clare Neilson Collection affords us, serve to reinforce my view.

We live out our lives relationally and our possessions can help us to articulate the narrative of our lives. Very often they reflect points of love and friendship in our journeys. In these ways they can help to ground us in this life, but it is important to remember that we are only the custodians. The Clare Neilson Collection and the generosity of its gift speak loudly of this and deserve to be celebrated.

‘Paul Nash – The Clare Neilson Gift Exhibition’ is on show from 9th April to 30th June 2013. For more information and opening times go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 10th April 2013 in the West Sussex Gazette.