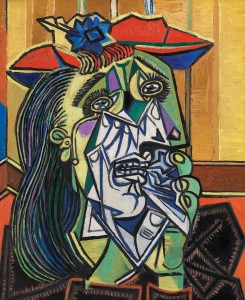

A remarkable exhibition opens this weekend at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. At its centre is one of Pablo Picasso’s most remarkable pictures: ‘Weeping Woman’. The painting was originally owned by the famous writer, artist and patron Roland Penrose, who made his home at Farley Farm House, near Chiddingly in East Sussex.

The exhibition, titled ‘Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War’, is the first to focus on the artistic response of British visual artists to this conflict and the common voice and influence they found in continental artists like Pablo Picasso and Joan Miro.

Roland Penrose helped to bring Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ to Britain. Its powerful depiction of the destruction caused by the German bombing of the defenceless town of the same name had a profound impact on the public and artists when it was shown in Britain in 1938 and 1939. Roland Penrose bought ‘Weeping Woman’ from Picasso. Painted by the artist in 1937, it is an iconic work which contains an innate and powerful response to the horror of the Spanish Civil War. ‘Weeping Woman’ was exhibited alongside ‘Guernica’ in Britain.

The Spanish Civil War was described by Stephen Spender as ‘the poets’ war’. It was recorded by writers like George Orwell in ‘Homage to Catalonia’ and Ernest Hemmingway in ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’. Hemmingway described the Spanish Civil War as ‘the dress rehearsal for the inevitable European war’. Simon Martin, exhibition curator and Pallant House Gallery Artistic Director, comments: “This was a civil war with an international dimension.” The British government signed a non-intervention treaty and was officially neutral. For many British artists and writers, however, the civil war went beyond an internal conflict between the democratically elected Republicans and General Franco’s Nationalist rebels. For them and many others in Britain, the civil war represented the wider battle against Fascism. “Many artists were concerned about the appeasement,” Simon explains. In scenes reminiscent of Quentin Bell’s painting ‘May Day Procession with Banner, 14 July 1937’, artists like Roland Penrose, F.E. McWilliam and Julian Trevelyan marched in the 1938 London May Day Procession to protest at our government’s policy of appeasement. They wore masks, made by McWilliam, caricaturing the Prime Minster, Neville Chamberlain. Simon Martin notes: “You will find one of the masks in the exhibition. There is an obvious and very palpable fear expressed in these artists’ works, a fear that the rise of Fascism in Germany, Italy and Spain would lead to something which would much more directly involve Britain.”

Against the backdrop of these internationally turbulent times, the artists’ response is personal and charged with emotion. I ask Simon about this quality. He pauses for a moment and replies, “It is rare to work on an exhibition in which so much of the work is about deeply held matters of politics and conscience. Their response provides a deeply moving articulation of this story of human tragedy, refugees, political prisoners and victims of bombing.” These themes are powerfully reflected in this exhibition.

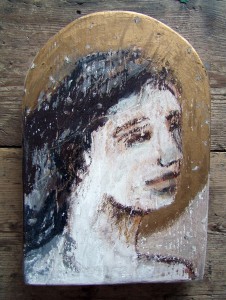

The show reveals to the viewer the effect of Picasso’s imagery on British artists. Take, for example, the surrealist Hopton Wood stone sculpture ‘Spanish Head’ by F.E. McWilliam. Here the mouth and eye of a head are distorted, reflecting the destructive power of this war. Henry Moore’s ‘Spanish Prisoner’, again influenced by Picasso, is equally disturbing in its depiction of human suffering.

‘Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War’ contains not only paintings, prints and sculptures, but also banners, photographs and ephemera, which bring to life the role of British artists in this civil war in a foreign land. It marks the 75th anniversary of the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939.

The timing of this exhibition’s opening is particularly poignant as the nation pauses this weekend, on Remembrance Sunday, to remember those who have fought and given their lives for our country and freedom.

‘Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War’ runs from 8th November 2014 to 15th February 2015 at Pallant House Gallery, 9 North Pallant, Chichester, PO19 1TJ. For more information go to www.pallant.org.uk or telephone 01243 774557.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 5th November 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.