Hans Feibusch represents a figurative tradition in 20th century art, which has sometimes been overlooked in favour of abstraction and other modern artistic expressions. He also has an important place in the history of a revival in church patronage of art in the Modern British Period.

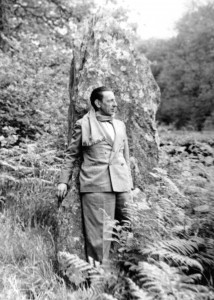

Hans Feibusch arrived in England in 1933 from Nazi Germany to escape persecution as a Jew. He had become an established painter in Germany, being awarded the German Grand State Prize for Painters in 1930 by the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. His talent was soon recognized in England and he exhibited regularly, often with the London Group, to which he was elected in 1934. The London Group included many of Britain’s leading artists.

His first public commission came in 1937 when Edward D. Mills invited Feibusch to paint a mural, ‘Christ washing the Disciples’ Feet before the Last Supper’, for the new Methodist Hall in Colliers Wood, London. The painting attracted a great deal of interest from the national press and brought the artist to the attention of Kenneth Clark, later Lord Clark. Clark was very influential and was director of the National Gallery in London during the war. His television series and book ‘Civilisation’ would subsequently capture the imagination of a generation.

Bishop George Bell of Chichester wrote to Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in 1939 asking for suggestions as to artists who might be prepared to accept commissions. Clark introduced Feibusch to Bell and the two men met for lunch in Brighton on New Year’s Day 1940. It marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship, during which Bell would be Feibusch’s leading patron. Both men were unprepared to turn their backs on evil. Feibusch personified Bell’s deep and active concern for the plight of the Jews in Germany and its refugees.

In 1929 Bell became Bishop of Chichester, bringing with him the patterns of worship and the arts from Canterbury Cathedral, where he had been dean. He wished to see churches filled once more with colour and beauty. Eternal truths could be proclaimed anew in music, modern art and poetry. More people would be drawn into the Christian community by the revival of this old alliance and renewed vitality. Among visitors to the Bishop’s Palace in Chichester were Gustav Holst, Vaughan Williams, Henry Moore, Hans Feibusch, T.S. Eliot, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.

Bell and Feibusch’s very particular friendship blessed Sussex with a number of murals by this artist, which can be seen at St Wilfred’s, Brighton, Chichester Cathedral, The Bishop’s Chapel, Chichester, and St Mary’s, Goring-by-Sea.

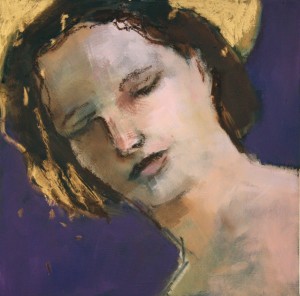

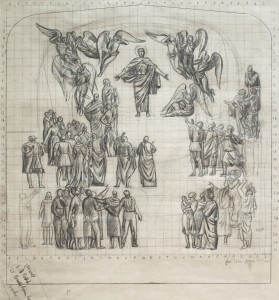

Painting onto the walls of churches and cathedrals requires painstaking preparation and the pencil cartoon by Feibusch shown here gives us a valuable insight into his work. It is a sketch for the mural ‘Christ in Glory’, painted in 1957 at St Sidwell’s, Exeter. Most striking to me are the prompts from Feibusch’s earlier works in Sussex. ‘Christ in Majesty’, also shown, was painted in 1954 at St Mary’s, Goring-by-Sea. Like in the sketch for St Sidwell’s, it displays Feibusch’s knowledge of Renaissance artists, whose influence is displayed in this mural. The Mediterranean lilac-blue, ochre and terracotta hues serve to emphasize Christ’s own pose, his arms open in a gesture of welcome and embrace. The figures are convincing, almost sculptural, with a quality of mass and light. Feibusch’s painting gifts them with a grace and nobility through their poses, which to some can seem to deprive them of life and passion. At first glance there is little that is unexpected but, as we look more closely at the angels, we note that the expressions on some of their faces are less angelic and more mischievous, acknowledging his depth of insight into the human condition, which can reflect good and evil. In the St Sidwell’s sketch, men and women look up to Christ with gestures of praise and thanksgiving, reminiscent of the figures painted in the Ascension scene painted by Feibusch in the Bishop’s private chapel in Chichester.

While the attention of the art world moved on to focus on the abstraction of Ben Nicholson and the new depiction of naturalistic forms by artists like Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland, Hans Feibusch continued to paint and draw in his own particular figurative style, influenced by the Renaissance. His style of painting has been the subject of renewed interest in recent years, with retrospective exhibitions held at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, in 1995 and more recently at the Bishop Otter Gallery, University of Chichester, in 2012.

The murals deserve to be celebrated. They represent the work of a gifted artist whose life is inexorably bound up with the extraordinary history and events of his time. For me, though, it is Feibusch’s sketches and drawings that reveal his true talent.

Hans Feibusch’s work rarely comes to the market and so it is with some excitement that I am looking forward to Toovey’s specialist fine art sale on Wednesday 12th June, in which the St Sidwell’s ‘Christ in Glory’ sketch and a number of other studies and prints by the artist will be auctioned.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 5th June 2013 in the West Sussex Gazette.