One of the best known of all Japanese woodblock designers is Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). Hiroshige’s landscape prints are internationally acclaimed and are amongst the most frequently reproduced of all Japanese works of art. They are defined by their unusual compositions and humorous depictions of people involved in everyday activities. His exquisite observation and depiction of weather, light and season are exemplary. Hiroshige’s work proved hugely influential for many leading European artists including Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh.

Hiroshige worked in the latter part of the Edo or Tokugawa period (1603-1867). The Tokugawa shogunate had become the unchallenged rulers. It resulted in what has been described a ‘centralized feudal’ form of government.

In contrast to this agrarian society a vibrant community of merchants and businesses grew up in towns and cities in the early and mid-19th century, at the time Utagawa Hiroshige was working.

For the first time urban populations had the means and leisure time to support a new culture of theatres, geisha and courtesans. This search for pleasure became known as ukiyo (the floating world), an ideal world of fashion and entertainment. Pictures and prints depicting images of the everyday in this new society became known as Ukiyo-e – scenes of the floating world. However, Hiroshige’s depiction of people is recurrently bound up with the landscape.

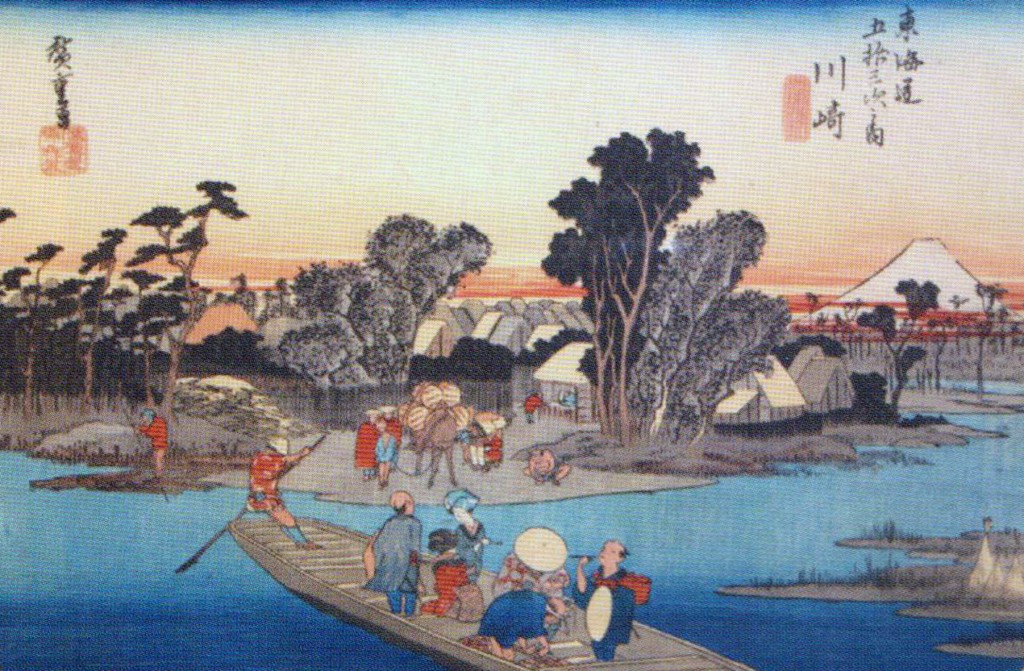

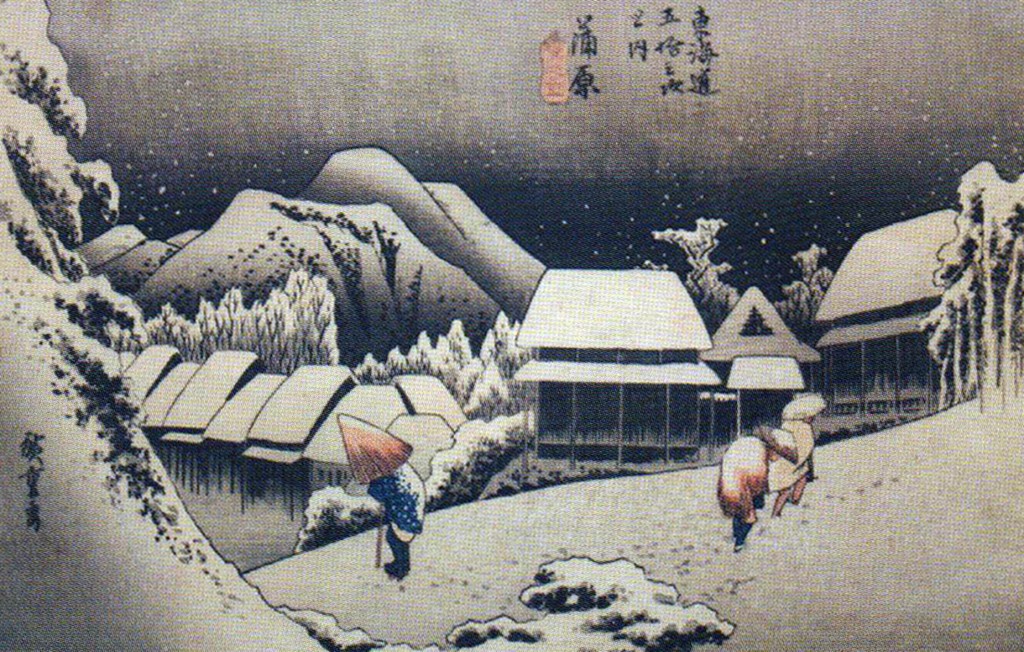

Hiroshige combined his print making with his inherited position as a fire warden. In 1832 he was invited to join an embassy of Shogunal officials on a journey which allowed him to observe the Tokaido Road, the Eastern sea Route which followed the coast through mountain range to Kyoto. The resultant series was called ‘Tokaido Go-ju-san-Tsugi’ (The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido). The three prints illustrated are early states of the polychrome woodblock oban prints from this series. They date from around 1833.

Oban refers to the most common size of Japanese print usually measuring approximately 23.5cm x 36.5cm.

The production of Japanese woodblock prints involved the artist, whose design would be pasted to the block so that the engraver could cut it. Straight grained cherry was often used as it allowed for fine detail to be carved. The printer would then print the image. As many as ten blocks were used to achieve the diversity of colour. At each stage of the process proofs would be made for approval.

Hiroshige’s lyrical depiction of ‘Night Snow at Kambra’ is poetic. We are left with a sense of the stillness and silence which often accompanies snow. It is late and no lights are apparent in the houses below as the villagers trudge home.

In contrast ‘Rain storm at Shono’ portrays farmers and porters running for shelter as the sudden downpour of rain darkens the sky and obscures the mountains. The figures, angle of the rain and the wind in the trees, lends the image a sense of urgency and movement.

In ‘The Rokugo Ferry at Kawasaki’ we witness pedlars and women on a pilgrimage, in a ferryboat. On the far shore a laden pack-horse and palanquin wait, with Mount Fuji on the horizon beneath the sunset.

These three examples formed part of a collection of eight polychrome woodblock oban prints from the The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido series by Utagawa Hiroshige. There is always a premium for early states and they realised a total of £17,500 in two lots at a Toovey’s specialist auction. Blocks would often be altered and reused. These later states can still be bought for a hundred or two and represent wonderful value for the potential collector.

This important artist dominated Japanese landscape printmaking and was a major influence for many leading European artist.

Utagawa Hiroshige’s scenes so often depict travellers along famous Japanese routes providing us with captivating sights. But it is the intimacy with which he portrays people in snow and rain in all seasons which never ceases to delight me.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 8th April 2015 in the West Sussex Gazette.