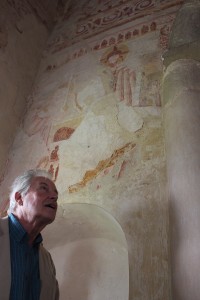

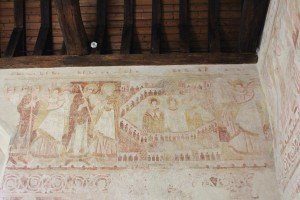

With Christmas approaching, I have come to see the remarkable painted interior at St Michael and All Angels church at Berwick in East Sussex. I want to reflect once again upon Vanessa Bell’s beautiful depiction of the Nativity.

The fine decorative scheme was commissioned by Bishop George Bell of Chichester. Bell was a great patron of the arts. He wished to see churches once more filled with colour and beauty. Eternal truths would be proclaimed anew in modern art, poetry and music. More people would be drawn into the Christian community by the revival of this old alliance and renewed vitality. Bell founded the Sussex Churches Art Council. Relying on generous patrons, like the famous economist John Maynard Keynes, he began to commission work. Keynes was a frequent visitor to Charleston, where Duncan Grant had a great influence on his artistic sensibilities. Visitors to the Bishop’s Palace in Chichester included Gustav Holst, Vaughan Williams, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and T.S. Eliot.

During the summer and autumn of 1940 the Battle of Britain was fought over the skies of Sussex. The Luftwaffe failed to defeat the R.A.F. but the Germans continued the Blitz into the May of 1941. Against this backdrop, Bishop Bell commissioned Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell to paint St Michael and All Angels. The parish church at Berwick is just a few miles from the artists’ home at Charleston.

Writing to Angelica Bell in 1941, Vanessa Bell proclaimed that Charleston was “all a-dither with Christianity”. Large panels were prepared to be painted on in the barn at Charleston. Family, friends and neighbours were used as models.

Initially the project met with local opposition but Kenneth Clark and Frederick Etchells acted as expert witnesses and the scheme was accepted. At the time Kenneth Clark was director of the National Gallery in London and Surveyor of the King’s Pictures.

The visitor today is met with a scheme of paintings in the Renaissance style. They depict scenes from the New Testament, which include the Annunciation, Christ Crucified and Christ in Majesty.

Vanessa Bell’s Nativity sets the familiar Christmas story of the birth of Christ in the folds of the Sussex Downs. The scene is painted in a barn beneath the Firle Beacon. Local shepherds posed for the panel. Their distinctive shepherds’ crooks are typical of those made at Pyecombe since medieval times. Vanessa’s daughter, Angelica, is depicted as Mary. St Luke writes: “Mary treasured all these things and pondered them in her heart.” Here Mary looks on, preoccupied with her thoughts. Many people have suggested that the baby Jesus is reminiscent of Vanessa’s son Quentin, but I have often wondered if she was thinking of her older son, Julian. Julian Bell, a poet, had been killed in the Spanish Civil War. Peter Durrant, a local farm worker, is painted as Joseph. He lost his left arm as the result of an accident in which he fell from a wagon. To his right are three children, who worship at the crib in their school uniforms. They are Ray and Bill West, sons of the Charleston gardener, and John Higgens, son of Grace, the housekeeper. The stable is lit by a lamp at the foot of the composition. The lamb below is a symbol for Jesus, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.

Berwick’s Nativity brings to life this timeless, much-loved and familiar story, placing it in the heart of Sussex. It also remembers the joys and sorrows, and the hopes and fears of this community of people. Like the first Christmas, the season remains a time of gathering, reflection and remembrance. A time of shared memories and stories.

The Rector, the Revd. Peter Blee, will be celebrating a candlelit Midnight Mass, which starts at 11.30pm on Christmas Eve, and a Family Holy Communion at 11.00am on Christmas Day. St Michael and All Angels is one of my favourite places to stop and pray when I am in the east of our county. My thanks go to the Revd. Peter Blee and his congregation, who make this a living, prayerful place of pilgrimage for us all.

I wish you all a very happy and blessed Christmas!

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 24th December 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.