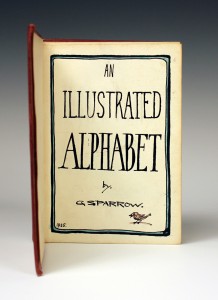

Geoffrey Sparrow was a doctor living in Horsham with a particular talent for drawing. His pictures often express his love of horses and hunting and provide a witty insight into country life in and around Horsham between the wars.

My family moved to Horsham in the 1960s from Pinner and Harrow, a story common to many at that time. In those days Horsham was still very much a provincial market town with its wonderful, faded, Regency theatre and houses where Swan Walk stands today. The town centre was on a human scale, rich in its vernacular architecture and independent shops. I have fond childhood recollections of watching the Crawley and Horsham Hunt riding out from the Carfax on Boxing Day. The smell of the horses, the colours of the hunting coats and the sounds of hooves on the road, huntsmen’s horns and barking hounds all remain vivid in my memory. I imagine that the town’s atmosphere then had changed little since the days between the First and Second World Wars, when Geoffrey Sparrow was practising as a doctor and making his prints, paintings and drawings.

Geoffrey Sparrow was born on 13th July 1887 in an age of trains and horses, not cars. He grew up in Devonshire and lived for foxhunting. He studied medicine at Cambridge and Bart’s but the Great War disturbed the procession of his life, as it did for many others of his generation. Sparrow volunteered and was accepted by the Admiralty as a temporary surgeon in the Royal Navy in September 1914, bearing the rank of Surgeon-Lieutenant. He served with distinction in numerous campaigns and was awarded the Military Cross, though he never described the events that led to this decoration.

Sparrow was demobilised in 1919. He had thought to specialise in London after the war but his former chief advised that, as he was then thirty-three and unknown in medical circles, he would be better off taking his Edinburgh Fellowship and practising in the provinces. Sparrow enjoyed his time in Edinburgh, which for him had the added appeal of a bit of grouse-shooting!

In those pre-NHS days, Dr Sparrow journeyed south to Horsham, where he joined the old family practice of Messrs Vernon and Kinneir. Well-liked and well-respected, he served prosperous families and schools in the area, like Christ’s Hospital. In addition, he attended to local tradespeople, undertook Poor Law work and public vaccinations and held a part-time position at the infirmary. Foxhunting with the Crawley and Horsham Hunt remained his passion.

During the Second World War he again engaged in military service. At the end of the war he retired from medical practice to devote time to his hunting and art until his death in 1969. Geoffrey Sparrow’s evocative pictures represent a warm and witty commentary on his times. The work is of exceptional quality with a sense of movement and line which delights collectors, especially from Sussex.

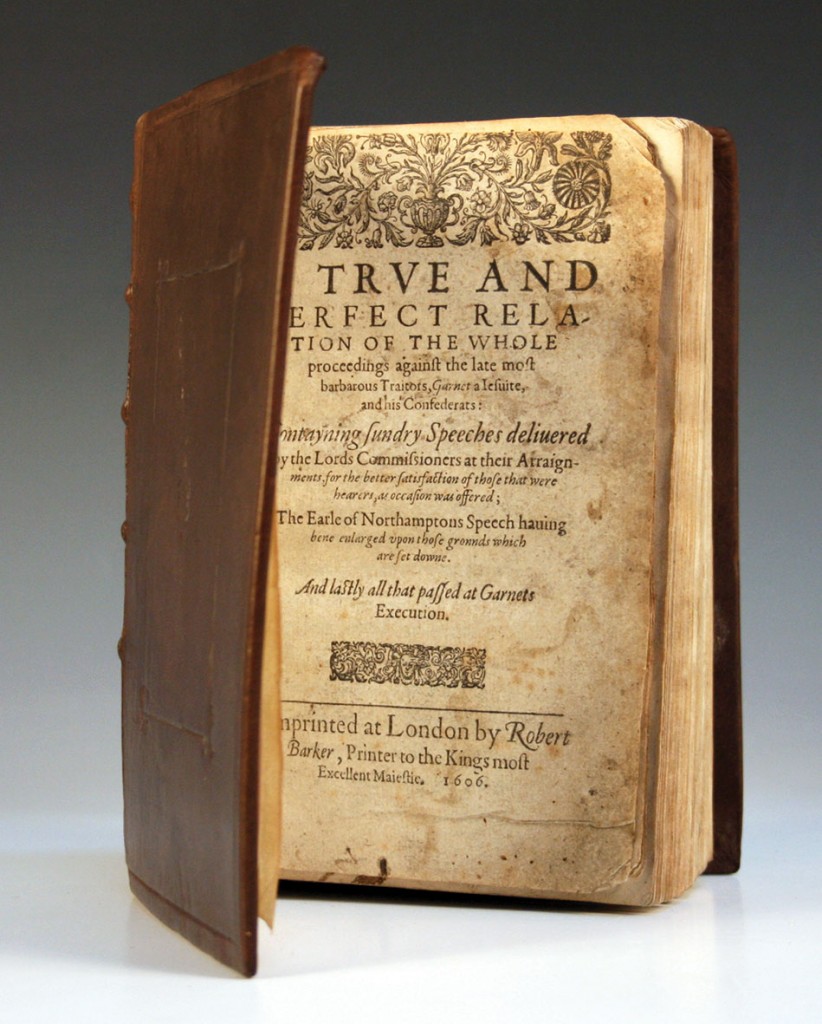

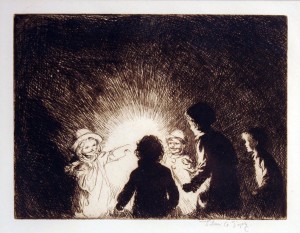

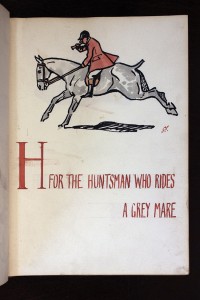

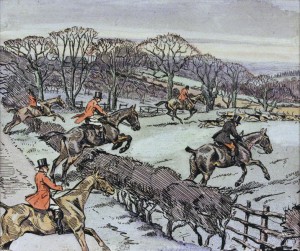

I am excited that a private collection of some twenty-one examples of his work have been entered into Toovey’s Christmas auction of fine paintings and prints to be held on Wednesday 4th December 2013. Pre-sale auction estimates range from £50 to £500. One of my favourite entries is this book, An Illustrated Alphabet, estimate £300-500, with hand-painted illustrations by Sparrow in watercolour and gouache; the page “H for the Huntsman who rides a grey mare” seems particularly apt. The hunting theme continues with the dry-point etching A Scurry in a Pewy Country, estimate £150-250, which shows Sparrow’s skill as a printmaker.

Dr Geoffrey Sparrow’s work, like the man himself, is regarded fondly around Horsham and further afield. It is worth mentioning how fortunate we are that the wonderful Horsham Museum and Art Gallery has a fine collection of his work, as well as his war medals. For more information, visit www.horshammuseum.org

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 20th November 2013 in the West Sussex Gazette.