The current exhibition Down from London: Spencer Gore & Friends, at the Brighton Museum & Art Gallery, draws on the gallery’s significant collection of Camden School Group paintings to re-tell the story of the celebrated and influential ‘Exhibition of English Post Impressionists, Cubists and Others’ which put Sussex at the centre of the Modern British Art movement.

Between 16th December 1913 and 14th January 1914 the Brighton Art Gallery became London by the Sea. The Camden School, under the presidency of Spencer Frederick Gore, was invited to select the work for the exhibition. It was a group of artists always given to creative divisions and was born out of the Fitzroy Group, New English Art Club and the London Group. It was the first time that Post-Impressionist and Modern art was shown outside London.

Walter Sickert had acknowledged that scope for ‘the free expression of newer artistic thought’ was needed. The original exhibition’s title highlighted the artistic divisions within the group which caused it to be divided into three rooms.

The first two rooms contained work by those in the more traditional camp of Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman and Lucien Pissarro. It is these sections of the original exhibition that the current show focuses on.

The third ‘Cubist Room’ had a separate introduction written by Wyndham Lewis. In it he embraced Futurism and Cubism. This section of the exhibition included major works by Jacob Epstein, Eric Wadsworth, David Bomberg and C. R. W. Nevinson. Sickert and Pissarro were appalled by this new work.

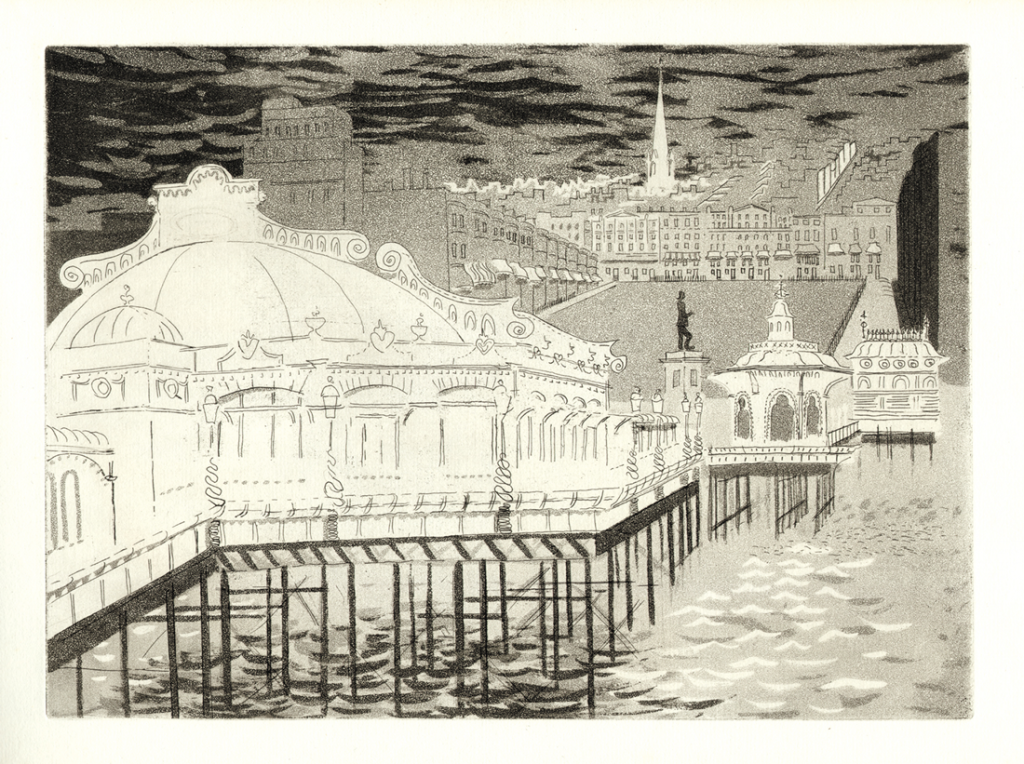

Amongst my favourite paintings in the current exhibition, and one which was in the original show, is Spencer Frederick Gore’s West Pier, Brighton which he painted in 1913. The scene shimmers in the brilliant light illuminated by the bold, blocky use of colour given life by Gore’s use of short, visible brushstrokes built up in textural layers.

Harold Gilman was also a central figure in the Camden Town Group. In his painting The Coral Necklace he employs a thick impasto applying the paint in generous blobs and smears. The rich pink wallpaper sets the tone of the painting but it is the red coral necklace which focuses our attention on the sitter’s face and hands. The portrait is thought to depict Gilman’s Austrian friend, Mary L. The scene is intimate and reflective.

Over a hundred years after the original landmark exhibition, Down from London: Spencer Gore & Friends revisits the influential work of the Camden Town Group. This beautiful exhibition runs until 11th September 2022. To find out more visit brightonmuseums.org.uk.