I have long admired the work of Sussex based potter Jonathan Chiswell Jones. An exhibition of his ceramics, titled “Earth, Fire, Gold: Elemental Beauty by Jonathan Chiswell Jones”, is being held at Chichester Cathedral until 14th September 2014.

Last week I wrote about one of our nation’s most famous potters, William de Morgan, who had such a formative influence on the 19th century Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain and a strong association with William Morris. He produced lustre wares, finding inspiration in Persian and Hispano-Moresque ceramics.

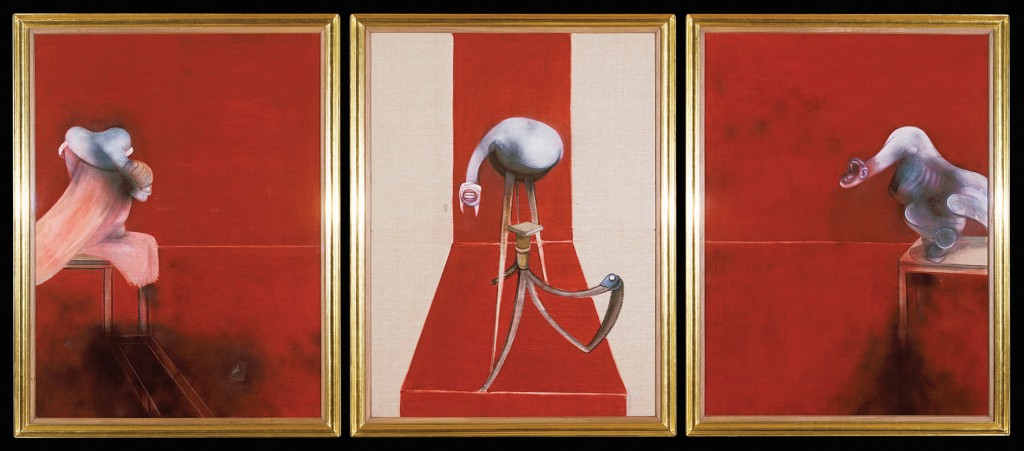

Like de Morgan before him, Jonathan Chiswell Jones is a master of carefully integrated patterns. These designs employ motifs drawn from nature, as in the dishes shown here with their reserve panels of flowers and fish.

William Morris famously said: “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” Good advice! Jonathan acknowledges the influence of the ideas of John Ruskin and the example of William Morris and says, “My aim is to make practical and beautiful porcelain and lustreware for use in the home. Making lustreware is a process of hand and head and heart; it is the challenge of practising a craft which utilises all my faculties.”

The dish inscribed “To Everything There is a Season and a Time for Every Purpose under the Heavens” draws its inspiration from that wonderful passage in the Old Testament from Ecclesiastes, chapter three, which has given such comfort to successive generations when they pause to reflect on the seasons of our human lives. The verses describe how God gives each of us things to do in his purpose and how we are to enjoy life as a gift of His Grace.

Born in Calcutta in 1944, Jonathan Chiswell Jones first saw pottery being made on the banks of the Hooghly River, where potters were making disposable teacups from river clay. He was one of Lewis Creed’s pupils. Lewis Creed was a young art teacher at Ashfold School, Handcross, who wanted to introduce his pupils to the joys of making pottery. Inspired by these early contacts with clay, Chiswell Jones has worked as a professional potter for the past forty years. In 1998, he was given an award by Arts Training South, which encouraged him to go on a course about ceramic lustre. He began to experiment with the thousand-year-old technique used by Middle Eastern potters to fuse a thin layer of silver or copper onto the surface of a glaze. This layer, protected by the glaze, then reflects light, hence the term ‘lustre.’ The lustreware on show at Chichester Cathedral demonstrates its continuing ability to capture our imaginations. Clay and glaze, metal and fire combine to produce pots which reflect light and colour, a process in which base metal seems to be turned to gold. Jonathan Chiswell Jones notes: “I am proud to stand in this lustreware tradition, with its roots in the Islamic empire of the 10th century, its appearance in Spain and Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries, its revival in the 19th century by Theodore Dec in France and by Zolnay in Hungary, and in this country by William De Morgan, and more recently by Alan Caiger-Smith.”

How fitting that, following in such an ancient tradition, Jonathan Chiswell Jones’ work should be displayed in our timeless Chichester Cathedral. William Morris defined art as “man’s expression of his joy in labour”. There can be no doubt that creating beauty in the world is part of our human purpose in this life.

“Earth, Fire, Gold: Elemental Beauty by Jonathan Chiswell Jones” is being held in Chichester Cathedral’s Treasury (next to the North Transept) until Sunday 14th September 2014. While you are there, take a moment to go to the Southern Ceramic Group Summer Exhibition in the Bishop’s Kitchen, adjacent to the Cathedral, sponsored by Toovey’s Fine Art Auctioneers.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 30th July 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.