The current exhibition at Pallant House Gallery, Hockney to Himid – 60 years of British Printmaking, is drawn from the gallery’s remarkable collection of prints gifted by the teachers Dr Mark Holder and Brian Thompson over twenty years.

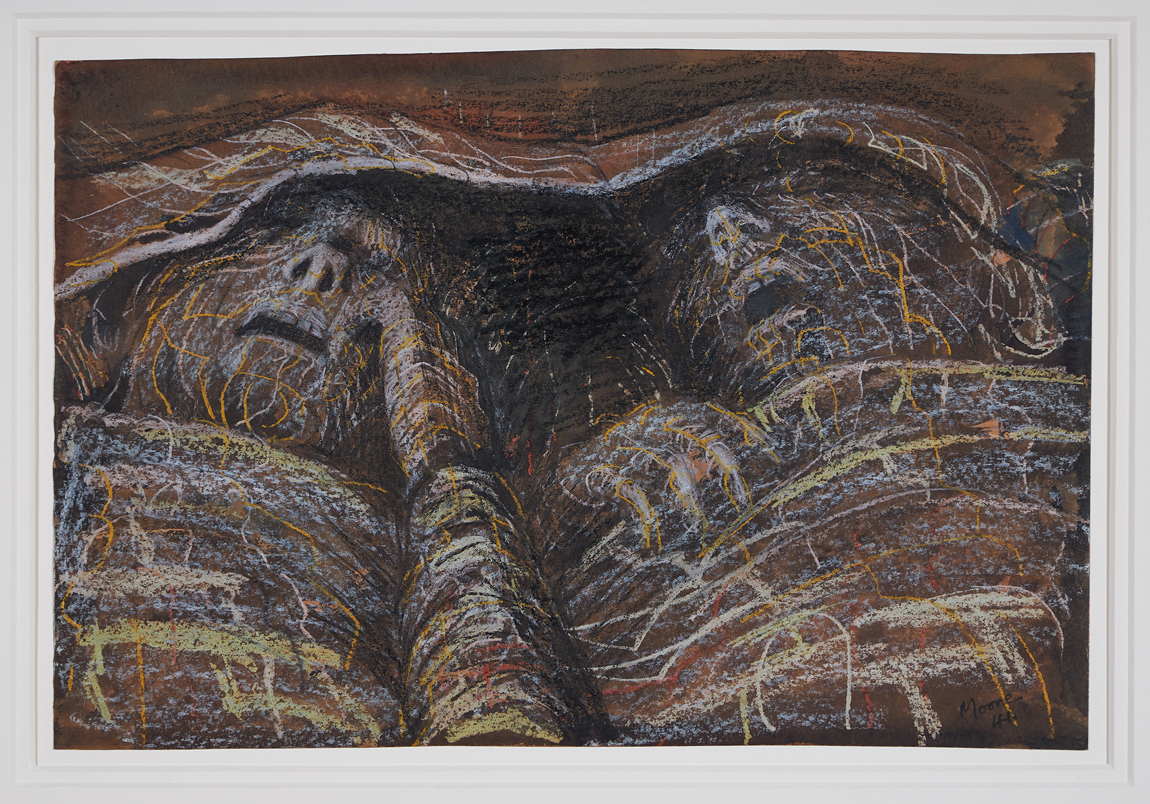

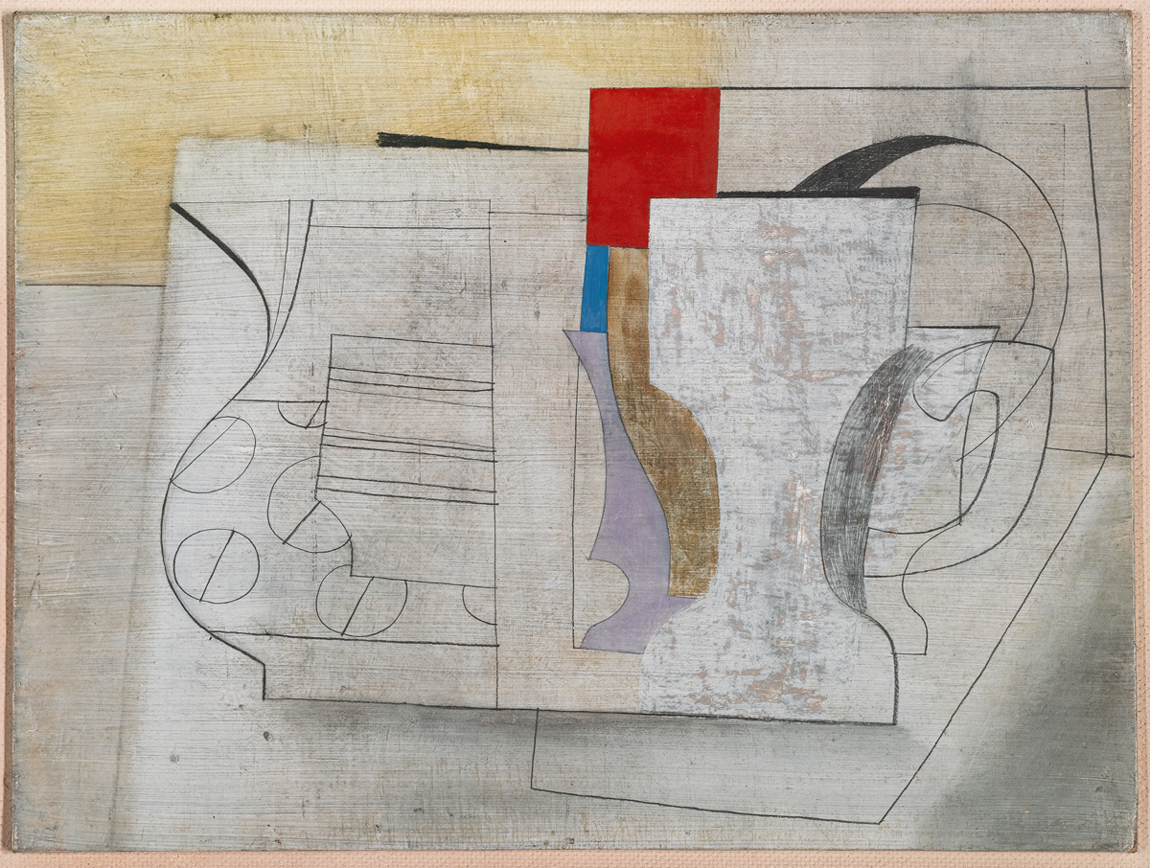

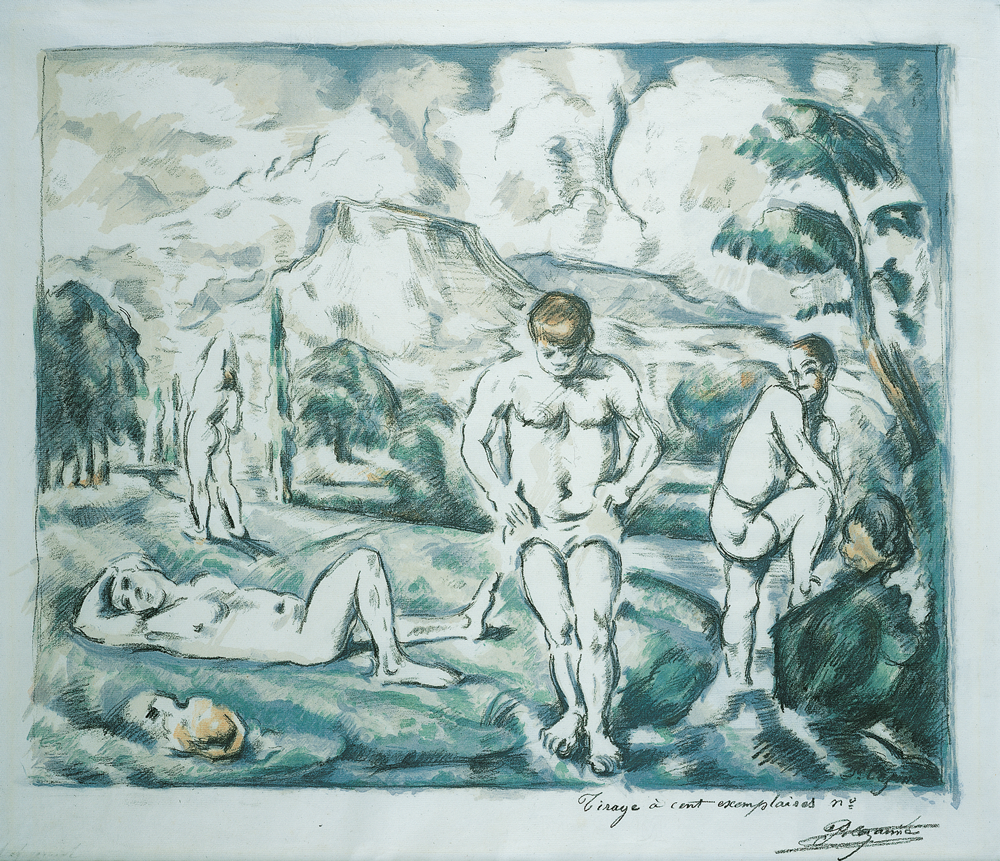

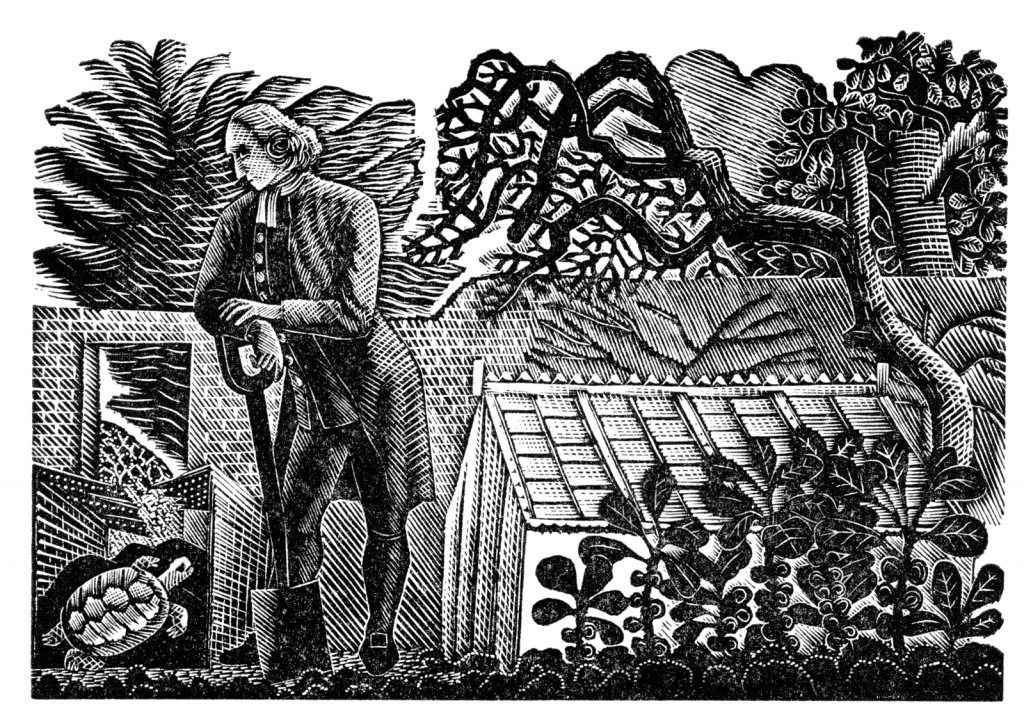

Across the centuries the world’s greatest artists have been drawn to the mediums of print. This exhibition focuses on the modern British artists of the 20th century including artists like Frank Auerbach, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, David Hockney, Richard Hamilton, Graham Sutherland and Lucian Freud. And from the 21st century contemporary artists like Paula Rego, Bridget Riley and Lubaina Himid.

This processional exhibition highlights the extraordinary breadth of expression of experiences in print.

During the 2020 lockdown Hepworth Wakefield commissioned a group of artists to create works to engage primary school children. Amongst these artists was Lubaina Himid who produced the lithograph Bird Song Held us Together. Commenting on the project she stated “It is vital that our young people can feel that they are important to us and begin to understand that we are all committed to investing in every way we can to help them expand and extend their potential.”

Over the last decade, Himid has earned international recognition for her figurative work. Her background in theatre design is often apparent. Her art and life is currently the subject of a major exhibition at Tate Modern. Described as ‘a cultural activist’ she explores Black experience and women’s creativity.

Himid often commentates on overlooked and invisible aspects of history and the experience of contemporary everyday life as in the lithograph on paper, Birdsong Held us Together. It is an expression and commentary on how important nature became to the national experience during the early months of lockdown. I am moved to remember how bird song rose like an anthem in the silence that accompanied the absence of cars and planes. The lithograph provides a powerful expression of a shared narrative. Common stories which bind us together as communities.

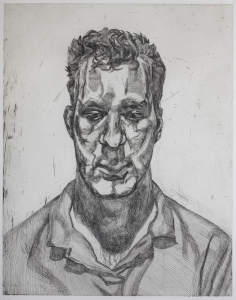

Lucien Freud’s highly personal study of his stepson, Kai, captures not only the physical but the emotional state of the sitter. Freud was close to almost all the people he portrayed. The studies were born out of lengthy, intense sessions which would last for hours over days or weeks.

Here, Kai is shown casually dressed against a stark background. The setting contrasts with the detailed depiction of his facial features. Although he had exacting standards for his etchings, Freud embraced unintentional marks transferred from plate to print and faint lines that came from modifications to the composition.

This generous exhibition born out of the gift of two teachers over decades is a delight to the eye and imagination. Hockney to Himid – 60 years of British Printmaking runs at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester until the 24th of April 2022.