Tate Modern’s current exhibition Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) shows the breadth of this artist’s remarkable talent as he embraced post-impressionism and gave a new and unique voice to the modern. The juxtaposition of angular lines and the richness of his palette are remarkable.

The exhibition provides a chronological perspective on his life and oeuvre. With more than eighty works on display it allows us to grasp the sheer audacity of this seminal artist.

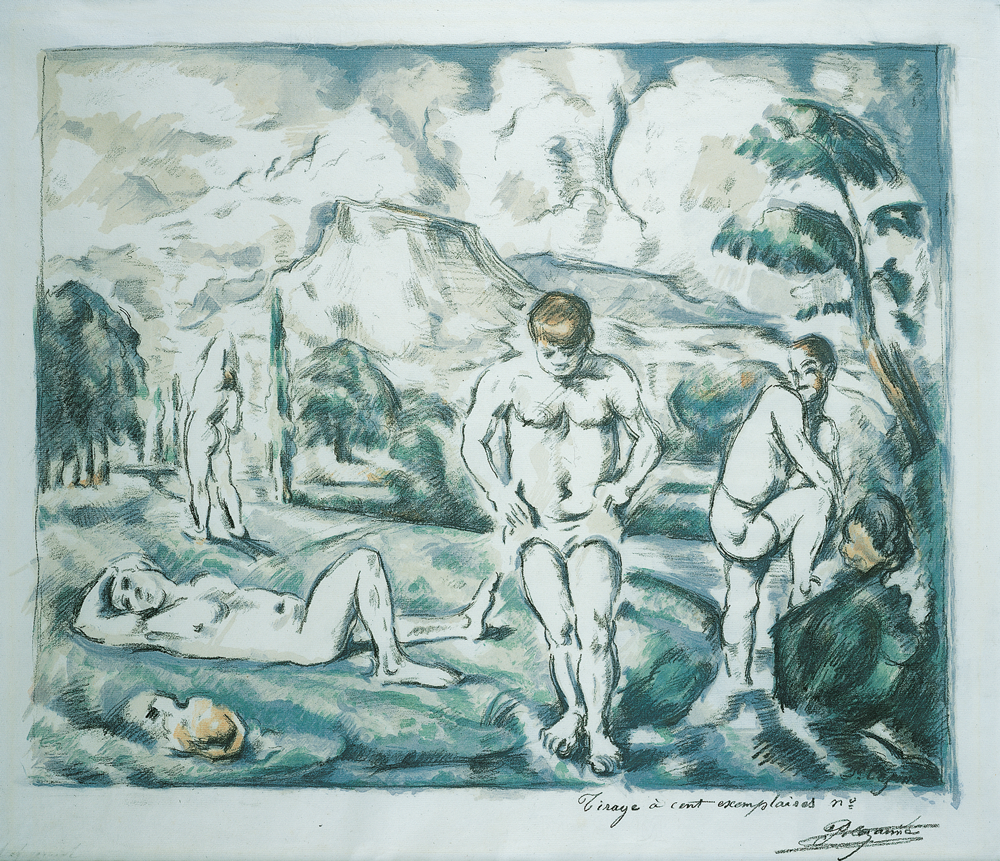

The exhibition reveals that all that Cezanne paints – the trees and landscape outside his studio in Aix, his family and those close to him, the fruit in his still lifes, the towering Mont Sainte-Victoire across the valley and even his late bathers – are painted in the context of Provence. Provence, as much an idea as a place, has gathered diverse peoples in her remarkable landscape over millennia. And they in turn, like Cezanne and his art, have been shaped by this remarkable place.

Cezanne is regarded by many as the father of modern art. His work foreshadows Cubism and Fauvism.

In Mont Sainte-Victoire the constructed painterly forms in the abstracted landscape gives voice to the artist’s emotional engagement with the rhythms in nature and the landscape. The painting is one of a group of landscapes taken from Les Lauves heights near the spot where Cezanne had a studio built for himself. In this scene our gaze is presented with a mosaic of differently coloured touches of paint. Green transitions into blues on the mountain face which rise harmoniously reaching for the sky. In the foreground the terracotta roof with the neighbouring green of the trees contrasts with the yellow sunlit walls; the shadows described in blue.

Writing to a friend in the 1890s Cézanne would declare “Art is a harmony parallel with nature.” Cezanne himself insisted that he painted from nature in response to his sensations.

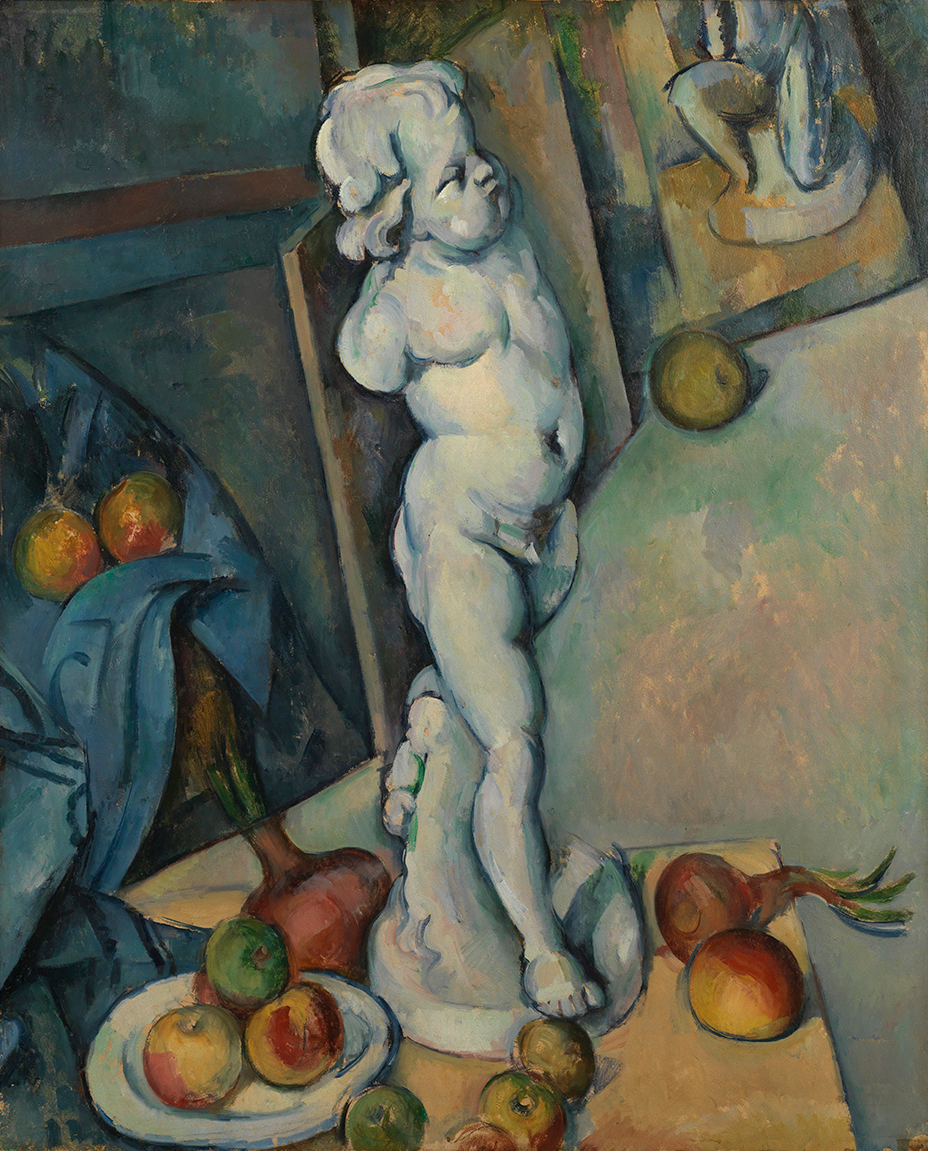

Also in the exhibition is Still Life with Plaster Cupid, one of Cezanne’s most complex later still lifes. There is an ambiguity in the arrangement of the objects. The Cupid stands on the table in the foreground whilst the floor appears to slope in an unnatural way; the green apple too large in the far corner. These paradoxes appear to heighten the sense of artificiality in the composition.

In Cezanne we glimpse the emerging modern.

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) is a remarkable exhibition and the first in a generation to examine this seminal artist’s work. It runs at Tate Modern until 12th March 2023.