It was my great pleasure to count the internationally acclaimed, Sussex-based artist Eric Mellon as my friend. Eric is most famed for his work as a potter and his pioneering use of ash glazes, but he also worked as a painter and printmaker. Eric was both artist and artisan.

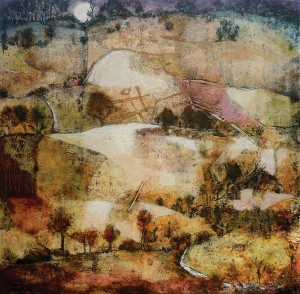

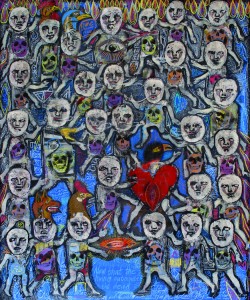

Over many years Eric strived to be able to transfer drawings onto his predominantly stoneware pots and dishes. He was always counter-cultural and believed strongly in the importance of narrative and fine drawing. His subjects drew on his Christian faith, stories from classical antiquity and his pleasure in the world around him. He also delighted in the human body, particularly the female form, which he depicted with honesty and fondness.

Years of research and experimentation into ash glazes brought him worldwide recognition as an artist, a ceramicist and a scientist. The ash glazes, especially those created with the ashes of certain bushes, prevented the lines of the brush drawings on his ceramics from bleeding during firing.

For Eric, his art was his calling. He embraced this path and everything in his life was bound up with it. Eric would recall how as a boy all he wanted to do was “to be an artist and to draw and paint”. At the age of 13 he won a place at Watford School of Art, where he studied until 1944. From 1944-1947 he attended the Central School of Arts and Crafts, where he met his lifelong friend, the Arundel-based artist Derek Davis. It was with Derek at a party held for art students that Eric met his wife-to-be, Martina Thomas. Martina was passionate about fine art and worked as a painter while Eric brought art and craft together through his pottery, drawings and prints. In the early 1950s he set up an artistic community at Hillesden, Buckinghamshire, with Derek Davis and fellow artist John Clarke. It was in 1951 that he began working increasingly as a potter. He married Martina in 1956. She was a gifted and talented artist and exhibited at the Royal Academy. They had two children, Martin and Tessa.

Eric, always an enthusiastic and generous teacher, ran summer art schools for some thirty years. In 1958 he set up a pottery at his home in West Sussex, where he worked for 56 years. To visit Eric’s studio and home was to be exposed to a lifetime of artistic endeavour and a riot of pottery, paintings and prints. He would say: “When I get up in the morning, I want, by the end of the day, to have created something new.”

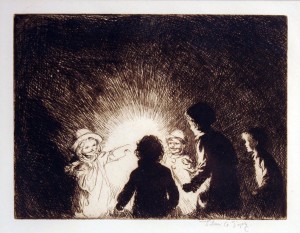

Often we compartmentalize our lives but with Eric art and existence intermingled; for him, work and life were one. So when you visited him, he would hold you with that particular care, keen to know about you and your news. Fondly and inevitably, though, your life in that particular moment would become bound up with his vocation – his art – for it was this that rooted him in this life. Later, in 2011, Eric wrote, “It takes many years to learn to draw, but eventually the pencil becomes a friend and, in a few minutes, moments in life can be recorded; these I call ‘frozen time’, as the sketches are no longer mere drawings.”

Eric came to the service at which I was ordained as a priest and informed me that he had made me a chalice. The symbol of Christ he drew upon it was, he said, designed to speak to all. It reflected the importance to him of communicating narrative. When I next called at his home, he presented me with it. I suggested that we celebrate a home communion there and then. Eric’s broad smile crossed his face and he accepted. We used his potter’s wheel as an altar, anointed the chalice with holy oils for use and celebrated our Eucharist.

Eric, in the foreword to ‘Pages From My Sketchbooks’, wrote: “Pages From My Sketchbooks records the joy of new life, the anticipation of pregnant women, the sadness of terminal illness, and the incredible moment when life departs the body into eternity… an artist records his life and shares it with everyone who cares to look.” His relationships with his family and friends sustained him at the end, as they had done throughout his life.

Eric Mellon’s work has been exhibited and acclaimed around the world, fitting recognition for this generous and gifted Sussex artist, who died on 14th January this year.

By Revd. Rupert Toovey. Originally published on 5th March 2014 in the West Sussex Gazette.